The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights includes work and education as basic needs for any person, without discrimination. In today’s world, neither can really be achieved properly without access to the internet. This is why UNICEF and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) joined forces in 2019 to create Giga, an initiative aiming to connect all schools in the world to the internet by 2030.

This article possibly couldn’t have been written (at least in a timely fashion) without the connectivity made possible by the internet. Research, file sharing, real-time conversations… So it is unimaginable and unacceptable that one in three people – around 2.7 billion worldwide – are still offline and without access to the internet. Among them are 1.3 billion children who are missing out on the information, opportunities and choices that come with being connected. The digital divide often leaves behind the most marginalised, pushing them to the fringes of the world.

In 2015, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted by all United Nations Member States, providing a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an urgent call for action by all countries in a global partnership. They recognise that ending poverty and other deprivations must go together with a certain series of strategies. Connectivity itself is not one of the goals.

“I propose SDG Zero: universal connectivity for all. We can’t achieve full gains in any of the goals without digital access.”

– Chris Fabian, co-founder and co-lead, Giga

With Giga, UNICEF and the ITU seek to promote digital literacy and equip students with the necessary skills to forge their future and fulfil their potential. Connecting young people to the internet allows for the exchange of ideas and experiences, encouraging a more inclusive global understanding through cultural reciprocity. In the last 18 months, more than 5,600 schools (over two million students) have been given access to the internet. The ambition for the next 18 is to connect a further 25,000 schools and more than 10 million learners.

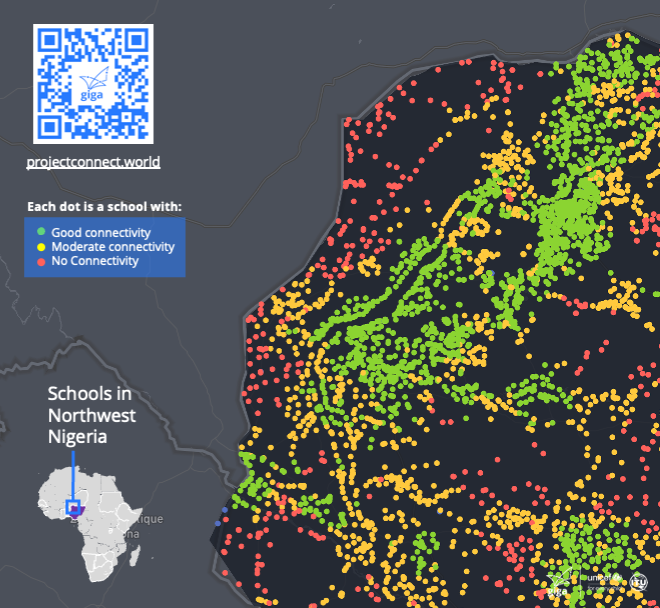

At its core, Giga is built on a new way of mapping the world and seeing digital inequity (www.projectconnect.world). Giga’s interactive map of the world shows school locations and connectivity as coloured dots: red for those without access to the internet, yellow for moderate connectivity, and green to represent schools properly connected to the internet. The map uses various techniques to locate schools, including artificial intelligence and machine learning, which comb through satellite imagery, identify schools and display them on a map (schools everywhere have certain indicators, including playing fields and early-morning queues of students).

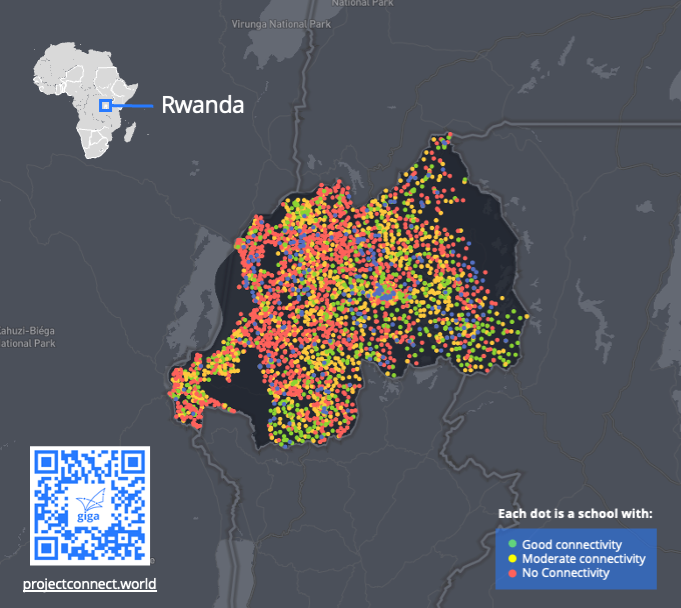

Giga’s interactive map shows school locations and connectivity as coloured dots: red for no access to the internet, yellow for moderate connectivity, and green to represent schools properly connected to the internet.

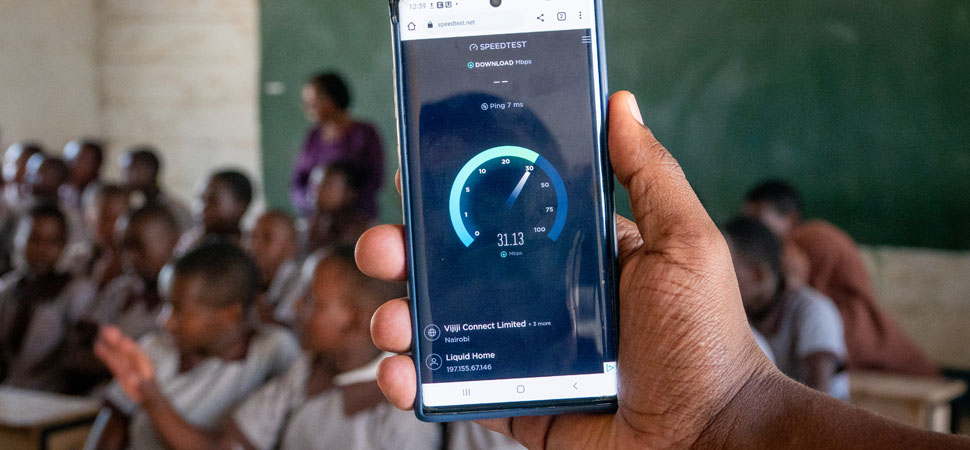

“Life before the internet was really chaotic,” says Head Teacher Peris Gaturi at Noonkopir

Primary School in Kenya. “It is something I wouldn’t wish to go back to.” Her school is one of the 5,600 connected by Giga in the last 18 months, and she has also witnessed performance scores increase by more than nine percent, attendance on the rise, and her own ability to send in exam scores and other administrative information eased because she no longer needs to walk miles to an internet café.

“No one knows how many schools there are in the world,” Fabian says. “For the 2.2 million schools we’ve mapped, governments and others can instantly see which are left behind.” Giga’s technologists, designers, finance specialists, product specialists and data scientists come from more than 30 countries and thrive on the fast pace of work in this “startup within the United Nations”.

Working with governments, new infrastructure plans are modelled. For example, in Kyrgyzstan, the government was able to use the mapping to reduce prices by as much as 43 percent, from $50 to $28.5 per month. The financing of connectivity is also supported by Giga. With its help, the Government of Niger is working to deploy $100m of World Bank financing for remote connectivity, and Brazil has had hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of financing unlocked in the last year. The final step is to help with the contracts that report connectivity status in real time to the Giga map and create opportunities for governments to manage their payments better and more clearly – not only for schools but also, in the future, for other public facilities.

All this serves to reduce the price of a gigabyte in a school. Some of it is due to new technologies, like low-Earth orbit satellites, driving prices down, but Fabian add that “it’s also due to the ability to aggregate demand and do bulk purchasing as more governments see internet as a vital commodity that must be provided to their learners to prepare them for the future.”

A UNICEF staff checks the speed at Nonkoopir Primary School in Kajiado County, Kenya. The school has Internet speeds of up to 31 Mbps, which is beyond the recommended minimum speed of 20 Mbps.

Giga is supported by various public, corporate and private entities. Major supporters include The Elon Musk Foundation, Ericsson, Dell and IHS Towers. Further support from Switzerland and Spain has allowed it to set up a Geneva HQ and a Technology Centre in Barcelona. To date, Giga has mobilised $1.1 bn to connect schools in 20 countries, utilising additional funding from institutions like the World Bank, Islamic Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, local governments and UNICEF country offices, among others.

Besides these sources of financing, Fabian adds, “We believe that Giga as such needs a capital allocation vehicle – a fund – to help us invest in some of the hardest-to-invest-in places – markets where traditional investment funds don’t see opportunity. This fund would help move money to emerging markets and build up the basic infrastructure so other investments could come in.”

While funding is key to Giga’s success, it is also about a collaboration of resources and the exchange of skills and knowledge. Two of their key corporate partners are Ericsson and Dell Technologies; both companies have contributed significantly, with their individual conversance spanning connectivity, mobile operator data, science analytics, high-performance computing and AI algorithms.

Rwanda is a good example of a country where Giga has changed the lives of millions of children. The map above shows every school in the country; the information is shown in real time. Paula Ingabire, Minister of ICT and Innovation in the cabinet of Rwanda, said during the 2022 UN General Assembly, “This tool makes it easier for the public to hold governments and internet providers accountable. With the help of these maps and Giga’s support, the government of Rwanda has made school connectivity 400 percent faster and 55 percent cheaper.”

Chris Fabian with H.E. Paula Ingabire, Rwandan Minister of Information, Communications, Technology and Innovation, and President Paul Kagame looking at a digital map of the country showing the schools that are online.

Giga is the only named initiative of the UN Secretary-General in both the UN’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation and Our Common Agenda documents, which lay out the plans of the UN and its member states with regards to digitalisation, technology and the internet.

That said, no project of this magnitude is without glitches. “We need to move faster,” Fabian admits. Giga cannot function efficiently without access to open data about public commodities (like the gigabytes that go to schools) and this access is proving difficult. “We need our government partners to quickly help us access their public data, or make it public, when it’s related to pricing for public goods,” Fabian says.

This ambitious and ground-breaking initiative has the potential to transform education in developing countries and is necessary to achieve a more equitable and sustainable future. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the critical need for internet access to support remote learning, as students throughout the world were forced to switch to online classes.

“Schools are centres of learning and hope,” Fabian concludes. “It’s where children learn skills to set them up for success later in life. It’s where parents send their children to give them a bright future. But what chances do children have if their schools are isolated from a rapidly digitising world? It’s unimaginable that more than half of the world’s schools face this reality because they are still offline. And it is even more unacceptable if humanity can finally see the problem and still is not moving quickly enough to solve it.”

Show Comments +