The Privateer mission was bound to happen, it was only a matter of time. Founded in 2021 by ex-NASA and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs Alex Fielding and Steve Wozniak (the latter also known as “Woz” for being considered a wizard of the tech sector), and Dr Moriba Jah, an astrophysicist and academic, Privateer is looking at providing general solutions to the new “grab” for space by commercial ventures. While the passenger flights might earn all the headlines, it is a very tiny fraction of the financial scale of the new astro-economy.

Despite the vastness of space, the area around this small planet we all inhabit is becoming overcrowded. What was once the splendid solitude of the occasional craft orbiting the Earth, has become a veritable congested superhighway of man-made objects. With the world’s billionaire’s now offering a variety of services: anything from Elon Musk and the subcontracting arrangements of SpaceX and NASA, to Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic which, apart from the passenger flight arm, also boasts a launch vehicle for satellite. Basically, the expectation is that the orbital paths around Earth are going to become ever busier.

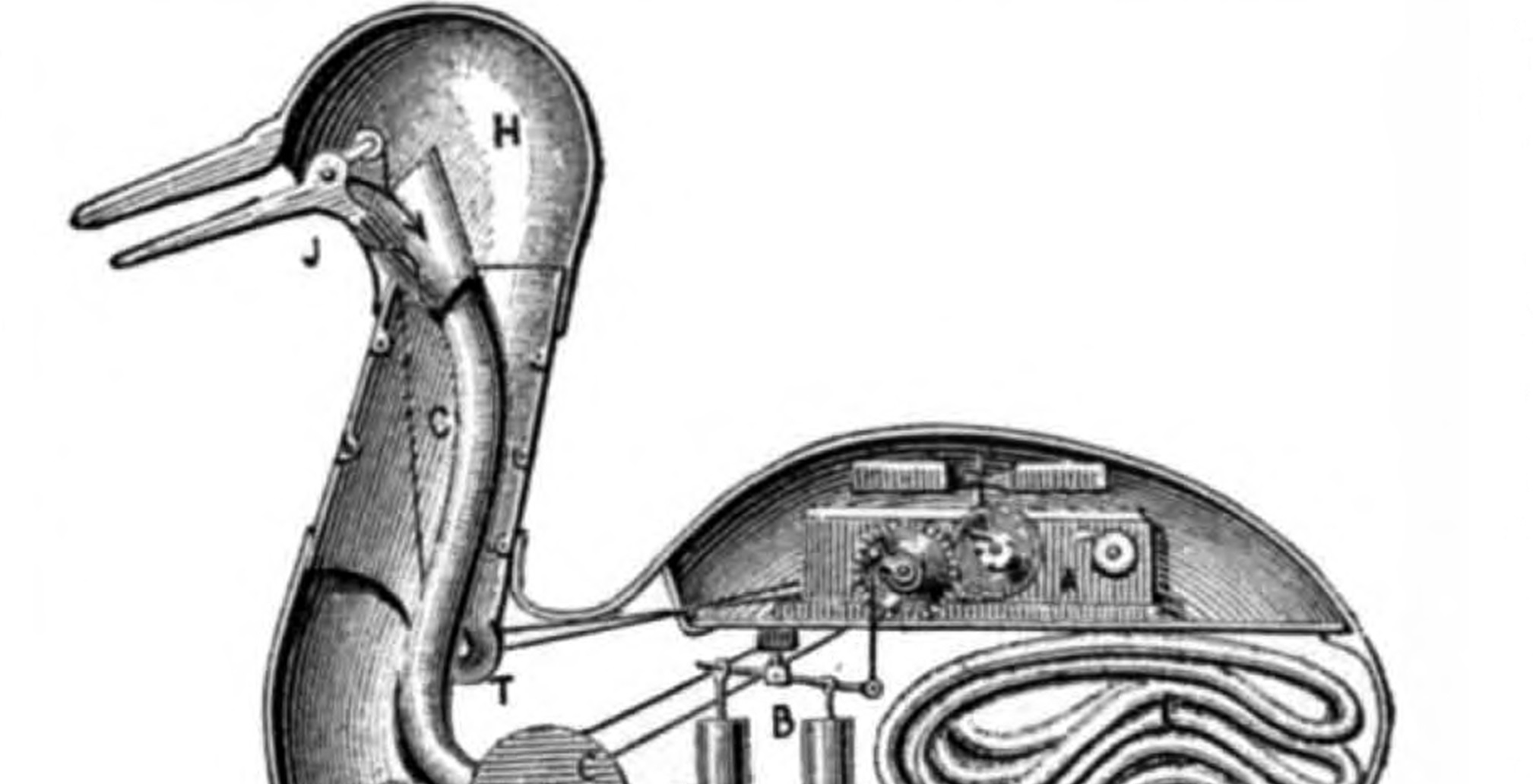

The area surrounding our planet is becoming a hazardous place with a second, commercial space age and as with any rush to the “new world” in the past, the newly discovered territories are getting busy. It is a problem of sufficient magnitude for NASA to have its own Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center, with their Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) satellites that measure the extent of “space junk”.

After six years and 57 experiments on space debris, NASA Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) was retrieved from Space Shuttle STS-32 in January 1990. © NASA

Equally, the problem is becoming more acute. In the next decade it is estimated that approximately 24,000 satellites will be launched. That is a lot of stuff floating around in an already overpopulated area. As the movie Gravity (2013) succinctly shows in the opening scenes, the danger of collision is all too real. Even the smallest objects can destroy or seriously damage a satellite given the speeds at which they travel. For example, orbital velocity at an altitude of 250 miles (400 km), where the International Space Station (ISS) flies, is about 17,100 mph (27,500 km/h) amplifying the impact force of even the smallest piece of debris.

The problem is the unknowing dependence on space for most of us. Anything from communication satellites – just look at your mobile phone and you are already one of those “dependents” – to weather pattern monitoring, financial system transactions and a host of other applications depend on devices that are up there. We might dream of a world where our mobile phone no longer harasses us, but we would also soon complain if the expected daily routine, where information provision is through the small electronic tag we all carry around, was no longer functioning.

Watch space debris in motion around the Earth, NASA Orbital Debris Program Office:

Dr Moriba Jah intended for Privateer to be set up from the altruistic conviction that it would take a common purpose to provide something for common benefit: “Privateer is all about enabling the collective intelligence of humanity. The premise is a belief that all things are interconnected; that stewardship is something that people need to embrace to solve these problems.”

Despite such charitable ideals, Privateer is the necessary commercial and technological venture that makes space safe and sustainable. It is very much a service for all, for everyone on planet Earth. Alex Fielding pragmatically noted that “I first started thinking about this company when there were 2,000 things in orbit, and about half of them were dead satellites. We used to joke that we would be the world’s first space sanitation engineers. Fast forward 20 years and no one did anything, as we all assumed someone would do something, and that’s heart-breaking. Institutionally we are a venture funded by fantastic firms, but our commercial business model is to enable access to space in a new, safe and sustainable way to operators and scientists alike.”

To provide the precision timing element, Privateer required a partner. Omega has a history second to none working and performing in space, as it does in the field of precision timing. Not only was their Speedmaster standard issue for the NASA Gemini EVA (space walks to you and me) and Apollo missions, but their technology has also been measuring sports events to ever increasing accuracy over the past 80 years.

Omega Skywalker X33 developed under a European Space Agency (ESA) patent licence, with astronaut Jean-François Clervoy.

This is not the first time that Omega will be in space to time objects precisely. Their instruments were aboard Skylab in the 1970s when the space station was orbiting the Earth and recording environment concerns with high resolution images. Even after the moon landing, Omega watches continued to be used for the European Space Agency (ESA) missions with the X-33 Skywalker.

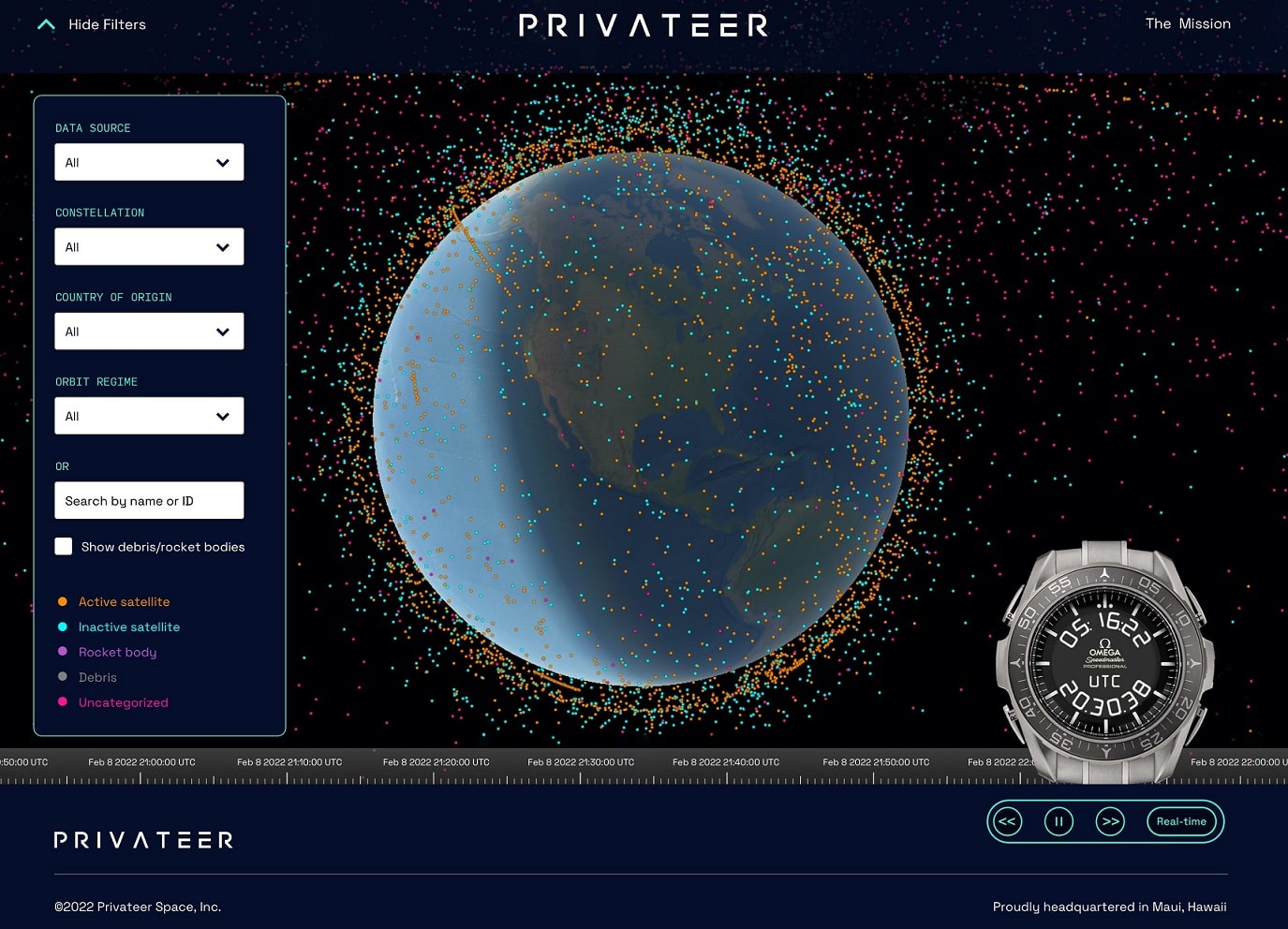

Recently, realising how the nature of exploration has changed, Omega has partnered with companies that are part of the new space economy. First, they are collaborating with ClearSpace, a Swiss company under contract with the ESA, to perform the first ever capture and removal of an uncontrolled satellite. Second, partnering with Privateer. Alex Fielding summed up why they chose Omega, “There are a number of reasons: first, helping us amplify the message of safety, stewardship, sustainability and space; second, on WayFinder, which is our tracking application, the first thing you’ll see is an X-33 with the UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) on it, keeping time that’s aligned with the clock from all the devices we track, which is incredibly important.”

There are a number of other technical and logistical considerations still to overcome. The first is that, while tracking the regular orbit of an object might be relatively straightforward, at some point the orbit will decay, and hence become uncertain. In Dr Jah’s mind, the problem is only one of finding the right variables. “There are events and things happening near Earth that we observe and need to know about. The data from those measurements and time data from Omega come into play here, provide structure or patterns that let us develop models. The models allow us to predict, and the difference between what we observe and predict constitutes surprise. The thing is, we’ll never be able to predict things exactly, but the process is iterative, and it’s one that is foundational to what we are doing at Privateer.”

In Gravity, American astronauts are left stranded in space after their shuttle is hit by high-speed debris.

The second part of the problem is that while an object’s orbital path can be tracked and the decay predicted, there are still other unknowns to the space debris currently floating around. The issue for Privateer is that this further complicates the problem of accurately tracking and cataloguing all objects around the Earth. Dr Jah provided an example. “Let’s take one element: propulsion. If they have slow propulsion or if they have fast propulsion, how much fuel do they have left, who has the right of way, who should be obligated to manoeuvre? These are very basic ideas on the ground. The public perception is that people who put rockets or satellites in space must know these things. It is the illusion of Star Trek and Star Wars, science fiction versus science fact. We must start to close the knowledge gap.”

To fill that knowledge gap, Privateer have developed free tools such as Relssek, an advanced conjunction analysis software that tells constellation operators when there is a collision risk, who is obligated to manoeuvre, and where the lowest risk position move is; and Glint Evader, which helps telescope operators identify and time their images to avoid satellites and other debris cutting through their shots. By making the capability pervasively and readily available to everyone, Privateer provides the service at a tiny fraction of what owning and operating a satellite would cost.

The public access screen of Wayfinder, courtesy of Privateer.com

The financial scale of what space will mean for us all in the next decade is out of this world. Privateer is unlocking the application layer of space both through software provision and the capabilities of the soon to be launched SuperPono satellites. It’s a long-term vision that Alex put into perspective, “If we rewind 10 years to the internet economy of 2011 there was a $250 billion marketplace about to be radically disrupted by Amazon. In a decade that market grew to $3 trillion.”

This is the effect technology can have on all aspects of the economy and of our daily lives, from the way we buy goods and services to how we travel or interact in social or business settings across international borders. Alex continues, “If we can help unlock similar scale and cost disruption on orbital access, we aim to take a $150 billion space economy today and transform it to a potentially $2 trillion market in the same timeframe. The applications being developed will help us on climate science, agriculture, safety, navigation, communications, insurance and far beyond. Imagine being able to have images of the coastline to determine erosion for the price of a pizza instead of a private jet. It’s that type of radical scale efficiency that will find a new generation of space entrepreneurs with the ability to build incredibly powerful apps we cannot even imagine yet. Think of it as rideshare.”

Words: Dr Andrew Hildreth

Opening picture: The Privateer Group – Dr Moriba Jah, Steve Wozniak, and Alex Fielding.

Show Comments +