Sandor Ellix Katz is a fermentation revivalist. His explorations in fermentation developed out of overlapping interests in cooking, nutrition, and gardening. He is the author of two best-selling books: Wild Fermentation and The Art of Fermentation, which won a James Beard Foundation award in 2013 and the recently published Fermentation as Metaphor.

Miguel Toribio-Mateas is a clinical neuroscientist and food science/nutrition researcher specialised in the relationship between gut microbes and mental health. He’s an advocate for diversity, not just when it comes to food, but in very aspect of your life. I-M Intelligent Magazine asked Miguel to interview Sandor, from one fermentation fetishist to another, the result was an eccentric and most interesting conversation encapsulated below.

I believe it’s safe to say that 2020 has been the year of fermentation… and not just in the literal sense. I mean, we’ve all been feeling very virtuous making our own kimchi and spreading it over homemade sourdough at Zoom dinner parties, trying to impress our friends with the size of our bubbles,“I ferment mine for an extra 12 hours, darling…” Beyond the banality of my jokes about traditional home baking lies my deep interest in the concept of “fermentation as a metaphor” which, incidentally, is the name of Sandor Katz’s new book, which couldn’t have come at a more relevant time because the sociopolitical kombucha we’ve been overbrewing worldwide for years has popped the lid off the Kilner jar right in front of our eyes; and it has done that at such speed, that we’ve not even been able to capture the moment so we could share it on TikTok.

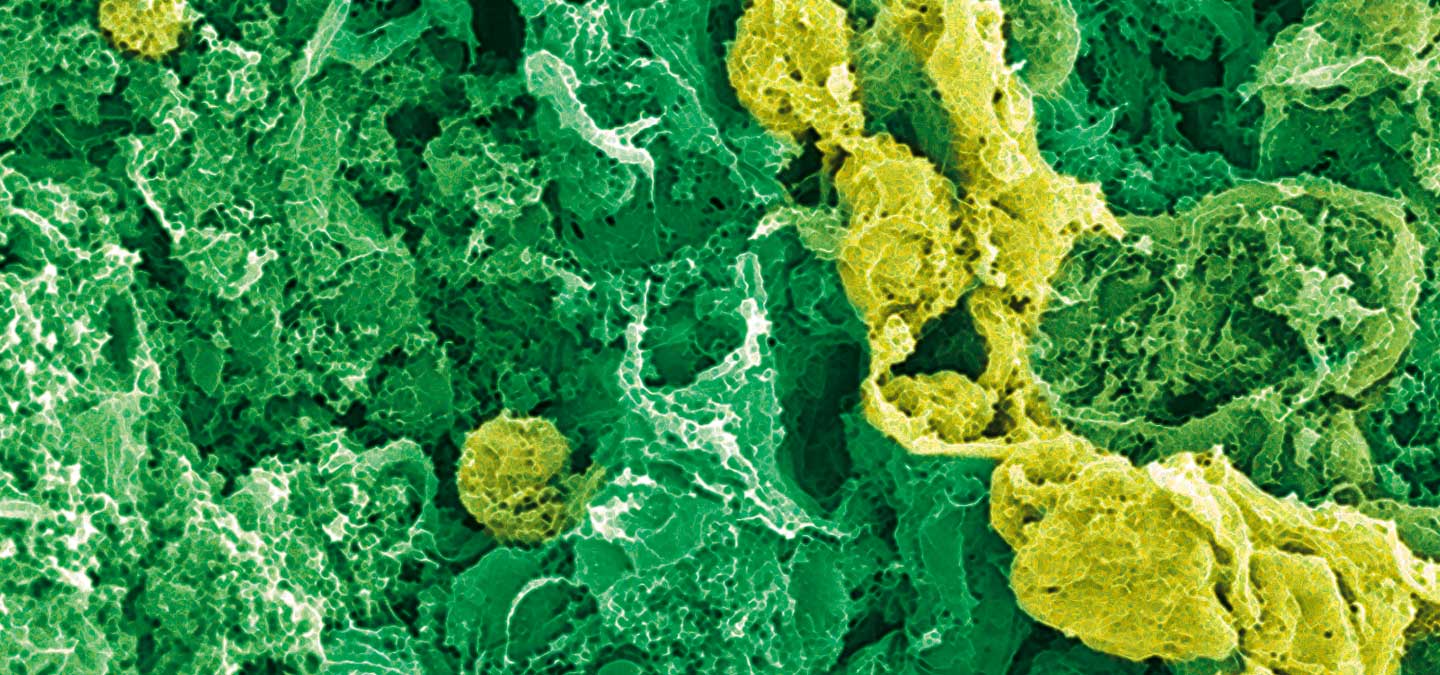

Where do I start? Protests in Hong Kong and Belarus, the Australian bushfires, Brexit, Covid-19, the BLM movement, the explosions in Lebanon, the disastrous oil spillage in the unspoiled Mauritius coral reefs… The world seems to have gone topsy-turvy, spinning out of control. So the huge surge of interest in fermentation is hardly surprising. Fermenting enables us to connect with the magic of the natural world, tapping into ancient rituals that humans have been performing for millenia. Fermenting is also about preservation and survival. Evolutionary biologists generally agree that humans descend from bacteria-like ancestors, so perhaps the turbulent times we’re living are making us reacquaint ourselves with the bugs we depend upon for functionality and maybe, survival too.

build your body’s cultural ecology as you engage and honour the life forces all around you

– Sandor Katz

The hour I had with Sandor felt like five minutes. We could have got lost in fascinating discussions about how microbial communities share so many similarities with different aspects of politics, religion, social and cultural movements, art, music, sexuality, identity, and even with our individual thoughts and feelings. But we also talked about fermented food, and about how his interest in them started in his 20s in New York City, when he experimented with shop-bought pickles and sauerkraut and realised how he could literally feel his mouth watering the moment he was opening the jar.

Sandor was referring to the cephalic phase of gastric secretion, which occurs before food enters the stomach, resulting from the sight, smell, thought, or taste of food. The greater the appetite for that food you’re about to eat, the more intense is the stimulation. And this is partly why pickles were good for Sandor, who tells me they really helped with his digestion. And that’s cool, but I didn’t want the interview to be about the benefits of fermentation. I am a scientist working in this field. I read papers about this all the time. I wanted something a big juicier than to ask Sandor for his top three vegetables for pickling. Ten minutes into the in the interview I was feeling like giving him a big hug because, even though we’re worlds apart, I was resonating completely with what he was telling me about ferments. There is this guy from NYC who now lives in a rural, off-the-grid queer community in Tennessee and me, “a Spanish Brit” neuroscientist specialising in the gut-brain connection, sharing stories about pickling.

I was telling Sandor about how my early childhood memories of mum and dad – originally from Jaén, Southern Spain – pickling olives in brine with garlic, orange peel, fresh fennel twigs and cumin seeds; and Sandor was telling me about how he grew up in a family that move to the US from Belarus, and how he got into fermentation not just because he felt that pickles helped his gut, but because of his overlapping interests in cooking, nutrition and gardening, which transcribed beautifully into his 2003 bestseller Wild Fermentation. In a way, it felt like meeting a whole lot of complete strangers in a club in London in 1994. They all came from different walks of life and you didn’t know anything about them but house music united the whole of the dance floor in a wild and wonderful way, so you just shared sweaty hugs as a way to say “thank you”, and to honour that experience. You left the club glowing, having satisfied that craving for diversity that we inherently carry in our DNA, a feeling that stayed with you for weeks.

I believe it’s safe to say that

– Miguel Toribio-Mateas

2020 has been the year of

fermentation.

In a much more politically correct 2020, fermentation gives us an opportunity to incorporate into our bodies that little bit of wild that our spirit craves, becoming one with the world around us, which is populated by trillions of microbes. The therapeutic powers of some of these microbes have permeated traditional health wisdom around the world. From Japanese tamari and miso, made with a fungus called kōji (or Aspergillus Oryzae for the geeks out there), to Eastern European kefir, a symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast with up to 60 different living bugs in it, to Sandor’s grandma’s sauerkraut, or the olives my parents pickled in Andalucía, all of these fermented foods represent a melting pot of diversity with great, unmediated life force that can make us help us adapt to shifting conditions and lower our susceptibility to disease. But they are also “a small antidote to homogenisation and uniformity you can undertake in your home, using the extremely localised populations of microbial cultures present there, to produce your own unique fermented foods,” Sandor tells me, a perfect chance to “build your body’s cultural ecology as you engage and honour the life forces all around you.”

I believe that colour and taste are perfect tools to express ourselves, so I asked Sandor what he thought about the now almost overused “eating the rainbow” phrase which, I must admit, I still love and use myself daily. “Fermented vegetables are a fantastic way to ensure access to colours provided by every season” he explains. Preserving winter foods into the spring, spring foods into the summer and autumn, and summer foods into the winter is a wonderful, ethical way to minimise waste and to enable our bodies to access nutrients that would otherwise be locked to that particularly season. This might appear simple, but it’s a wonderful way to think expansively about food and thinking of fermenting as a way to enable us to eat local. To get access to foods produced in our own garden during every season of the year, that to me is just magical.

Something Sandor said towards the end of our time together really encapsulated my feelings about fermented foods. Ferments can be incorporated into any kind of diet, regardless of its ideology. And there’s a little bit of something for everyone in ferments, whether it’s the taste, the nutritional properties, or the therapeutic effects. Vegetable ferments are ideal for those looking to live a plant-based life, whereas traditionally cured meats are less known products of traditional preservation and fermentation techniques in countries around the Mediterranean.

I could have spent the rest of the evening talking to Sandor and absorbing his immense knowledge on fermentation, exploring the intersections between culture, politics, identity and food. Sadly I couldn’t give him that big sweaty “good old raver’s hug” I so wanted to give him but sharing that Zoom screen with him for an hour definitely left me feeling warm and fuzzy inside. If you want to embrace your ferments and give your body a little bit of that antidote against homogenisation that your spirit craves, Sandor’s book will definitely give you that little push you need to go ahead and do that.

FERMENTATION AS METAPHOR

By Sandor Ellix Katz

Published by Chelsea Green

Hardback. £20.

Show Comments +