Edward Gibson was the last man out of Skylab. After 84 days orbiting planet Earth, floating inside the space station (at the time a record duration flight) he closed the hatch, entered the capsule with his crew mates and headed back home.

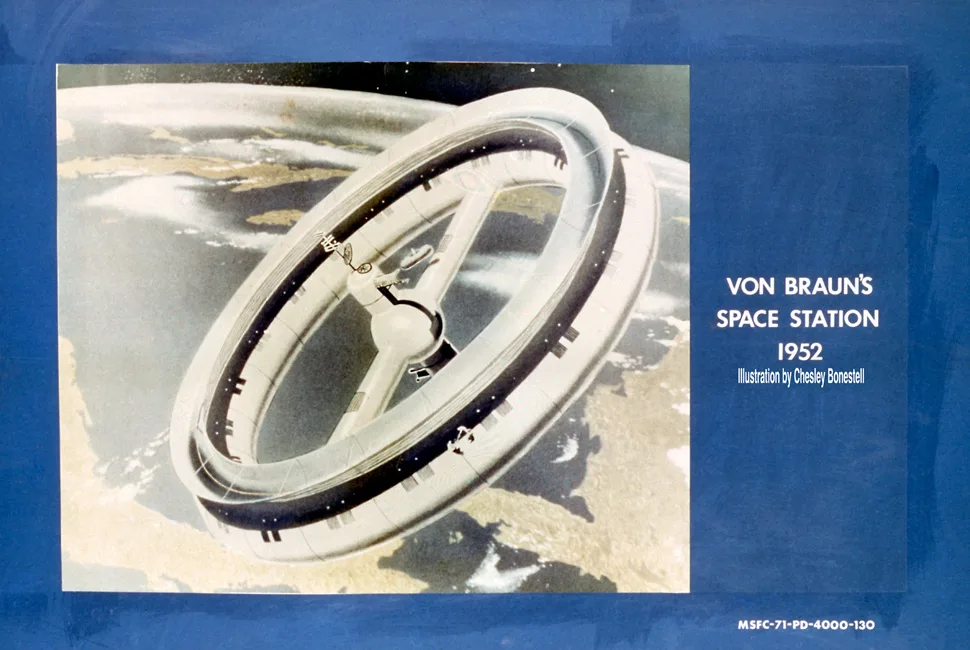

There was no ceremony, no parting goodbye ritual; as far as Gibson and the other two members of the crew were concerned, there would be others who would arrive and stay aboard the US space station. Gibson quipped, “We didn’t know whether anyone else was going to show up, so we didn’t leave some caviar for the record or something.” There had always been the expectation that an orbital station would be needed for space exploration. From rocket engineer Wernher von Braun (Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center and chief architect of the Saturn V rocket) to science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke, the intention was that any venture out into the vastness of the universe, be it the solar system, across the galaxy, or just a trip to the moon, a space station would be the departure point. In the 1950s von Braun participated in the publishing of a series of influential articles in Collier’s magazine, titled “Man

Will Conquer Space Soon!”.

Despite the hardships and dangers of being in space for so long, Gibson (now a spritely 84 year old) never tired of the view…

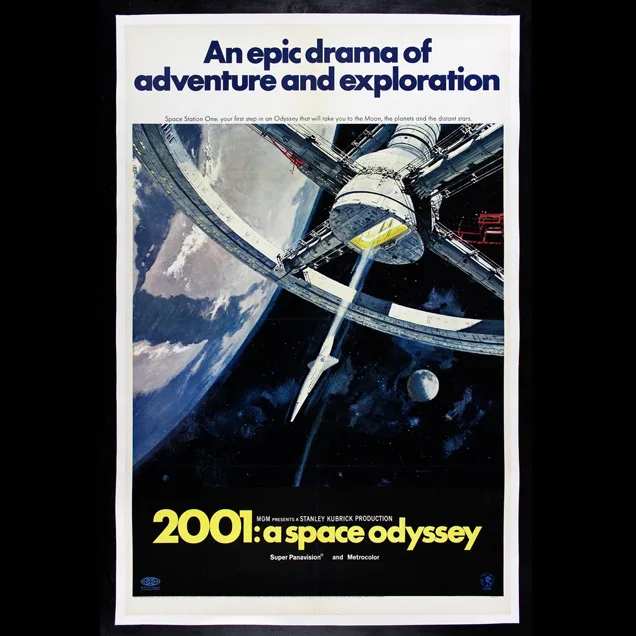

He envisioned a large, circular station 250 feet in diameter that would rotate to generate artificial gravity, which was considered important at the time because little was known about the effects of prolonged zero-gravity on humans. Made of flexible nylon, the large wheel-like space station would rotate above Earth in a 1075-mile orbit. The station was necessary for missions that included a juncture for space exploration, a meteorological observatory and a navigation aid. Certainly, Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick used the same visual in the movie classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Skylab was science fiction made science reality: humankind was learning to live in space beyond the approximate week and a half round trip to the moon. If the future for Earth’s inhabitants really did lie in the stars, then we had to start learning to live among them. While scientists and science fiction writers might envisage new worlds of serene space stations circling our planet, the economic, technological, and logistical realities dictated a more modest approach. Skylab followed the Apollo programme and while it did not resemble the initial ideas of what a space station would look like, it was nonetheless an ambitious and laudable first step into the exploration of the stars.

Fittingly, it was launched into low Earth orbit by a Saturn V rocket with the S-IVB third stage not available for propulsion because the orbital workshop (that looked like an oversized tin can) was built out of it. It was the final flight for the rocket more commonly known for carrying the Apollo moon landing missions. As its name suggests, Skylab was a space laboratory to undertake several hundred science experiments, a workshop, a solar observatory and some limited crew quarters.

NASA paid greater attention to the food available for the astronauts than they did in the Apollo missions. Gone were the “protein pill” approach to be replaced with food that was more flavoursome and textured. Part of Skylab’s mission was to observe human adaptability, ability to work, dexterity, habitat design and operations for prolonged space flight. The astronauts even had an onboard shower. Edward Gibson graduated from the University of Rochester in engineering before going to the California Institute of Technology for graduate work earning a PhD in the same subject with a minor in physics in June 1964. Gibson was selected as a scientist-astronaut by NASA in June 1965 and served initially as part of the backup crew to the Apollo 12 moon landing as well as participating in the design and testing of many elements of the Skylab space station.

Gibson had to wait until the third manned mission to have a chance to go into space as the science pilot of Skylab 4. The mission launched on November 16, 1973 and concluded February 8, 1974. The crew members celebrated Christmas in the space station and even unveiled a decorated makeshift tree for the festive season. At the time, it was a record-setting 34.5 million-mile flight, completing 56 experiments, including collecting Earth resources data using Skylab’s experimental camera and sensor array during their 1,214 orbits around the planet. Dr Gibson was primarily responsible for the 338 hours of Apollo Telescope Mount usage which made extensive observations of solar processes.

He also undertook three space walks during his time on board. Despite the hardships and dangers of being in space for so long, Gibson (now a spritely 84 year old) never tired of the view. Drifting high above the Earth for almost three months, Gibson reflected that “You get used to it, it seems like a very natural place to be. Being up there at that altitude, it feels very comfortable, very enjoyable and a great scene. What I really enjoyed was getting to know Earth like the back of my hand.

Regardless of how much you think you knew about it, until you really see it day after day, you don’t really feel familiar with it.” It is the one thing he misses the most, the serene and majestic flight around the world. Gibson elaborated further, “It really gives you a perspective of where you are and where you have been living. We really missed that when we came back.”

For Gibson, space exploration should be both a private and a public asset…

The dangers were always present, but not some- thing that Gibson was ever actively worried about, “You know before you ever go in. It’s always in the back of your mind in the same way as the dangers boarding a commercial aeroplane although it does not have the same odds of accidents. For us, something could happen in a flash and it is all over. At least you would not linger! But we were not preoccupied with the dangers.”

Space started to become uneconomic during the 1970s. Budgetary cuts delayed the Space Shuttle programme that ultimately led to attempts at saving Skylab being scrapped. Back at the time, the costs of reaching for the stars were only within the realm of superpower governments. However, in the last few years space exploration is back on the agenda. Most of the world’s prominent billionaires are now engaged actively or passively in the space industry. Any individual with a six-figure sum going spare can now book a seat on a sub-orbital or even an orbital space flight.

Ed Gibson believes that it is the technology driving the new economics of space travel. In much the same way commercial aviation started out about a century ago, the space industry is on a similar trajectory today. There are initial pioneers that are helped

by government and then as costs decrease the move to the full commercialisation of the industry becomes complete. “The technology has come down to an affordable level to make space exploration viable for billionaires. Elon Musk, he started with just private funds, but now he has a lot of government support so that SpaceX is another arm of NASA.” Equally, for Gibson, space exploration should be both a private and a public asset.

Whereas when Skylab was orbiting the earth, space flight was viewed as a public good for the benefit of all, the more recent privately funded flights are equally to be welcomed despite the potential environmental concerns. To Gibson it was a case of both sides being beneficial: “It depends – you have to do it intelligently in getting people and flights into space. There is a benefit to all. Not sure there are any environmental con- cerns. The carbon footprint from the space industry is very small compared to the motor vehicles. But you have a choice and you have to do it in an economical way.”

The space flight duration records have now been broken numerous times. International Space Station (ISS) crews inhabit the orbit- ing satellite for months at a time and there may yet soon be intergalactic voyages out into the unknown from such an axis point above Earth. With the new economics of space exploration there is now talk of missions that will extend far further than before. The success of NASA’s recent 2020 Perseverance is testament to their ambition. Ed Gibson was of the same belief, “In the long term I think humanity’s future lies in space. I am one of those crazy people who believe that once we can move off to other planets economically and easily, then we will set up stations there. It is going to take a while but it will happen.”

Any monumental undertaking requires a pioneer to take the first steps and Ed Gibson was one of them. Despite the suc- cess of unmanned space flight there is still a need for the human element. It has been a perennial question since the first Mercury programme at NASA. Gibson still carries the belief that human contact is unique and necessary, “If a person is there, they can make observations. You might not even know what kind of observations you want to make until the human eye and brain get there. There are elements about a place that might be overlooked if explored remotely, so you do not know until some- one is there. It is the human ability to make decisions on things that are unanticipated that make it necessary to be there.”

Unable to be re-boosted by the Space Shuttle, which was not ready until 1981, Skylab’s orbit decayed and it disintegrated in the atmosphere on July 11, 1979 scattering debris across the Indian Ocean and Western Australia. Gibson’s feelings on Skylab was not one of loss, but one of being fortunate to see what he had. The space walks were memorable, not least for seeing a comet fly by while on one of them but for simply being able to view our planet from space: “Feeling part of the larger world in which we all live. That was the never-ending impression of what I had, and I have always appreciated it.”

To watch the movie Searching for Skylab, America’s Forgotten Triumph:

Words: Dr Andrew Hildreth

Show Comments +