At the tender age of 24, glamorous Ella is literally breaking moulds in the automotive sector as one of the youngest female materials engineers working in the industry, specialised in corrosion science and metallographic fracture analysis. As a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) industries ambassador, Ella goes around schools inspiring kids to go down the Science route, explaining to them that like her, maybe one day they’ll make a living breaking and smashing things at the Norman Foster designed headquarters of McLaren in Woking. Beats the Piccadilly line commute to a beehive style office, doesn’t it?

From an early age, Ella’s curious mind was fascinated by all kind of mechanical artefacts and loved breaking things apart to see how they worked and putting them back together. Our Editor Julia Pasarón had the chance to interview her at the mothership itself, which looked stunning in the crispy light of a sunny winter morning.

I-M: What was that attracted you as a kid to mechanical things?

E.P: My father was really interested in cars, and he was always passing car parts around the dinner table what spiked my curiosity but my first love was Chemistry. I liked the atomic side of things more than I liked cogs and bolts.” As a STEM ambassador Ella, often goes to schools to speak to kids and make them see that they all can become engineers but also that not all engineering is done in overalls; that there is the theoretical side of things and the subatomic world, show them what you do in chemical and materials engineering with microscopes. At the end of the day, I may be an Engineer but I still like to be glam!

I-M: You said that your father was very much into cars, what sort of awoke your curiosity. When you started your engineering studies, was it clear that you wanted to go into the automotive sector?

E.P: Not at all. When I started studying, I knew that I wanted to solve problems and realised I’d probably go down the sciences side of things, as on the other hand, I wasn’t very good with words. But it was only at university that I discover Chemical and Materials Engineering and found out what these engineering courses could offer me; I could still enjoy learning about atoms whilst problem solving like an engineer. I then looked into aerospace and civil engineering but automotive almost felt like natural to me as I grew up around cars so when the opportunity at McLaren came up, I knew it was what I wanted to do.

Among other contributions, Ella provided the material specs for all supporting aluminium and steel brackets in the 720S…

I-M: Is it part of what you do at McLaren to look at what happens when cars crash badly?

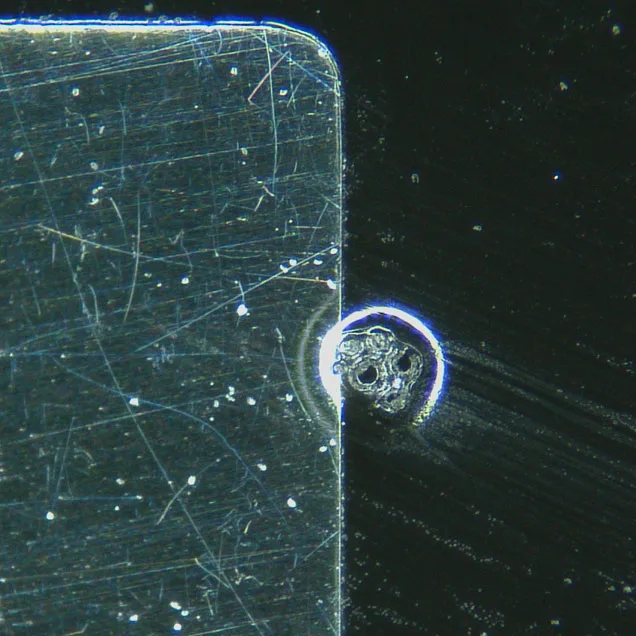

E.P: Oh yes! That’s a really key part of it, actually: from crash structures, all the materials, energy absorption in aluminium crash alloys, how carbon fibre reacts on the impact, how body panels deform… In fact I get quite a lot of broken things or I’m told to break and smash things up to see what happens to the different parts and materials. For example when something in a car is causing issues, often they’ll send the part straight to me to put it under the microscope and find out how the break started, and where the first crack happened, whether there was an external factor or not. The process is actually very straight forward: say something comes in broken, we will open it up on the fracture surface if it’s completely broken and from looking at it we can isolate where it originated. Basically it is a root cause analysis process.

For example, if there is a spot where the car got really hot, then we’d expect to find molten material and certain stress lines in it consistent with being affected by heat. By breaking the piece down like this we’d probably be able to trace back the fracture to other cracks and eventually find the root cause of the problem and find a solution, in this case, find a material with a higher melting temperature; and so we speak the relevant engineers and other function groups to take it from there.

I-M: So you work very closely with other departments, right?

E.P: Absolutely. I am really fortunate that I am in a position in which I can work at the beginning of the product process with the Design team, right through to the final stages with customer cars in the field, and lots in the middle stages such as testing cars under extreme conditions. For example, we take them to Dubai, Finland, or Norway to test our materials for UV degradation or some other potential cause of deterioration.

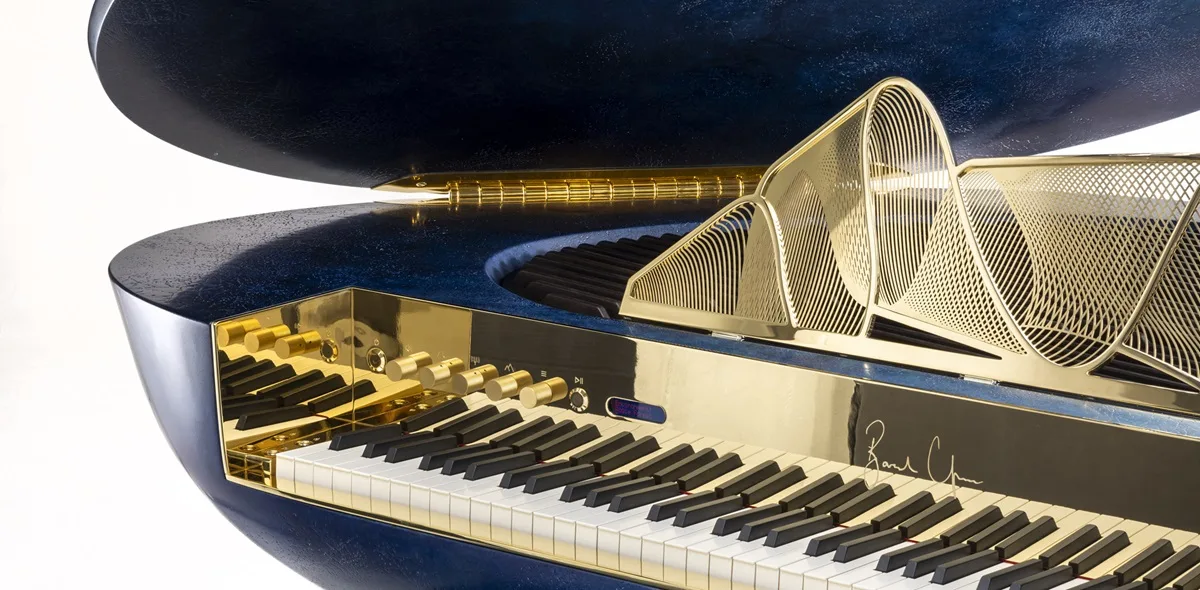

Here we are very that we’re able to work with a very wide range of materials: carbon fibre, magnesium, aluminium alloys and even gold, titanium or platinum, stuff that you wouldn’t necessarily get on other car companies, we get to experiment with.

When I started studying, I knew that I wanted to solve problems…

– Ella Podmore

I-M: Magnesium is highly flammable on certain conditions. How do you control that?

E.P: With magnesium, the trick is to completely isolate it, as with any other highly reactive material. The trick is to avoid contact with oxygen and/or water. This brings us to the technology of surface treatment and coatings; I do a lot of work on this.

I-M: Rowan Atkinson famously wrote off his F1. Presumably in that kind of high speed crash the magnesium can’t be anywhere near a potential leak of water or a naked flame. How do you ensure that is the case?

E.P: In a crash like that, it’s tricky to give guarantees, but in general, the parts of the car where we’d introduce a reactive metal would be quite clear off the fuel tank and stuff like that. However there is a common misconception with the likes of magnesium. When you’re looking at magnesium wheels and other things, people get very nervous, particularly with the history of the material in races like Le Mans, but the truth is that if you hold a naked flame to it, it wouldn’t catch fire.

This is what really interests me and challenges me in the lab: how can we get an exciting, lightweight material like magnesium, with the concerns about its flammability and brittleness and find solutions.

A resin bubble caused a defect in the manufacturing process…

– Ella Podmore

I-M: Given how different materials react to different conditions, does the level of bespoke service at McLaren include taking into consideration if the car just ordered is going to Dubai or to Finland?

E.P: Yes, actually, with MSO (McLaren Special Operations) we get a lot of very specific requests from VIP customers who are allowed to bespoke their cars to quite an incredible level and ask for certain parts coated in gold or some other precious material and we need to make sure that their material of choice will withstand the same conditions than the one we normally used would. I remember one client in particular who wanted a gold plated heat shield and I spent a few months figuring out how to get 24k gold to cope with the high temperatures that part of the car reaches.

I-M: Going back to crashing … how does a new car reacts to a crash in comparison to let’s say, a three year old car?

E.P: Theoretically no, because of the way we control our metals and the standards we set. Any metal, from three months to six, would show a bit of corrosion and slightly weakened strength. For this reason for example, we make each part endure 720 hours of salt spray tests and various other mechanical tests to ensure the performance of the material is superior to the load requirements of its application even after a prolonged time on the vehicle. However, there are always external and unpredictable conditions that you can’t account for.

I-M: You studied at Manchester University, the cradle of Graphene, one of the most exciting materials discovered in the last decade. In what direction are materials going in the automotive industry?

E.P: We are always looking for enhanced durability of materials, but I think at the moment the biggest push in the automotive market as it moves towards electric cars would be for light-weighting materials. This is something that Mike (Flewitt- CEO) always reminds us, that we want to be the lightest road car which obviously, is very exciting for me. It means I am always looking at new materials with lower density but equally strong. Carbon fibre is fantastic so I don’t think it is going anywhere. However, for some components where we cannot replace material with composites we are looking at making traditionally heavy car parts with much lighter materials.

I-M: There are not enough women in STEM industries. As an STEM ambassador yourself, do you think the number of females in these industries is growing at enough pace?

E.P: This is a good question. The number of women studying these subjects at University is definitely increasing but somehow, when you get into the industries themselves… half of them seem to have disappeared. Unfortunately automotive is slightly behind other industries such as aerospace and chemical engineering in terms of female: male ratios, but I think all companies are trying to do the right thing.

For example here at McLaren we have a women’s network which has worked fantastically in terms of support. . However I think we have to appeal to women earlier – when they are students – this way we can demonstrate what opportunities we have in the automotive sector and show it can be just as appealing (if not more!) than other industries.

When I go to talk to schools, kids aged 9-10 want to be astronauts or racing car drivers but then, they reach puberty and there is a switch away from all these fascinating futures to careers that are considered current in society, for like social media influencers, it would be interesting to understand how and why this happens.

I-M: So is the root of the problem in the educational system? Is there still a subliminal encouragement to maintain gender patterns?

E.P: Yes, and it is hard to break. I have seen it first hand. I believe companies are trying to do their best but while we still have young girls getting a pink toy and boys getting a blue car, we are unconsciously perpetuating the problem.

The same in schools, once puberty hits I have seen students revert back to stereotypical bias, Whether that be a result of their education or childhood I do not know, but I do know that this is an issue that needs to be changed by both teachers and parents.

I-M: What would be your dream project?

E.P: I love all the projects I am currently involved in, but I do love sport so maybe I’d like to have an influence on McLaren’s racing cycling team and apply what we learn to a different industry.

Also the “super material” Graphene is very close to my heart due to my links with Manchester, so integrating that technology into the supercars to put on the road would be a phenomenal project to get my teeth into.

Show Comments +