It seems simple enough, backgammon: a board game for two players where the checker-like pieces (referred to as “men”) are moved in contrary fashion around the board, governed by the random roll of the dice. A player wins by removing all their pieces (known as “bearing off”) before their opponent. The game’s outcome is a mixture of luck and strategy, but just how much luck, or which strategy, differs depending on the dice and the point of view of the individual.

The rules are easy enough to understand, but backgammon becomes complex when considering which move to make given your roll of the dice and the probabilities from your opponent’s turn. Backgammon has its origins in 17th-century England; its precursor is believed to be one of the world’s oldest board games, having been around for approximately five millennia. Archaeologists have discovered a 5,000-year-old board at the site of Ur, in modern Iraq. In Egypt, a backgammon set was found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

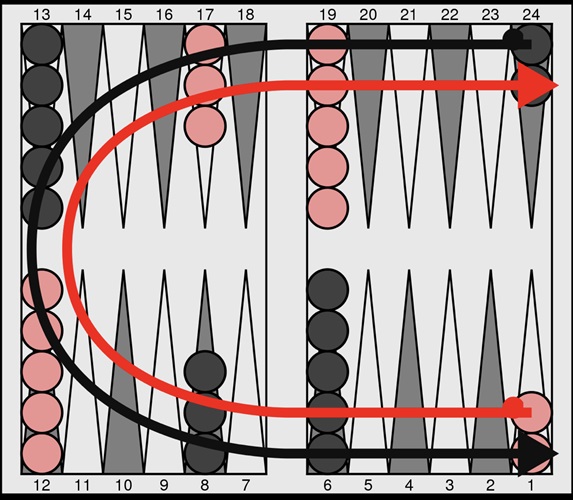

A diagram of the modern backgammon board indicating the direction of travel for the counters, to “bear off” and win.

For many eastern Mediterranean countries, the game has national and cultural significance. Popularity across the region has manifested itself as an oral tradition over time, where the numbers from the dice roll are announced using language derived from both Persian and Turkish. Backgammon became popular during the Ottoman Empire, and even today it’s a common feature of coffeehouses and social settings in the region. From the early 19th century, Damascus became known as the preeminent location for Damascene-style wooden marquetry backgammon.

In the Western world, backgammon’s immediate predecessor was a 16th-century table game called Irish, the Anglo-Scottish equivalent of the French Toutes Tables and Spanish Todas Tablas; the latter name, a translation from Arabic manuscripts, was first used in El Libro de los Juegos (1283). In English, the word “backgammon” is most likely derived from “back” and Middle English “gamen,” meaning “game” or “play,” and the earliest mention was under the name “baggammon” by James Howell in a letter dated 1635. The first documented use by the Oxford English Dictionary was in 1650.

An illustration from Libro de los Juegos, 1283, showing the game Todas Tablas, a precursor of backgammon

Elizabethan laws and church regulations prohibited “playing at tables” because it was considered gambling – even if the clergy were the worst offenders! It was in the 18th century, during the Age of Reason and the British deism movement, that backgammon found its natural home in this country, in the social and learned salons of the day. Edmond Hoyle, who also studied the rules for probability, published A Short Treatise on the Game of Back-Gammon in 1753, describing the rules and strategy. Hoyle considered it a game of computation and planning, and his pamphlet contained “a table of the thirty-six chances, with directions on how to find the odds of being hit, upon single, or double dice” so that, along with knowledge of the rules, “a beginner may, with due attention to them, attain playing well.”

For David Hume, the proponent of empiricism – the belief that humans only learn from experience – backgammon was more a game of random chance; the learning by doing that applied to human action did not do so for a game that was related to the roll of dice. In his An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), backgammon provided the antidote to ruminating over the “manifold contradictions and imperfections in human reason.” He explained, “I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours’ amusement, I would return to these speculations.” There was little in the way of reasoned strategy; it was more the enjoyment of play.

David Teniers the Younger, Game of Backgammon, 1640, © Cleveland Museum of Art

It was thanks to Prince Alexis Obolensky – “Obe” to his friends – whose family had fled Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution, that the modern game, with its organisation and authorised rules of play, came into existence in the mid-1960s. He co-founded the International Backgammon Association and in 1964 organised the first major international tournament, which attracted royalty, celebrities and the press. The game became highly popular, with tobacco, alcohol, soft-drink and car companies sponsoring tournaments. Even Hugh Hefner held backgammon parties at the Playboy Mansion.

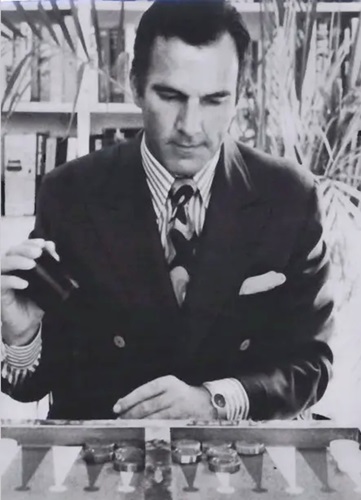

The newfound status – with sponsorship and prize money involved – saw the rise of professional players. It stands to reason that if backgammon is a game of pure chance, then players who earn their living from competing would not exist; over a long enough time horizon, the professional would fare no better than a rank amateur. Since 1967, there has been a world championship, and the sartorially resplendent Tim Holland was the initial holder of the title, winning the first three tournaments in a row. Holland was definitely of the opinion that he was playing strategically. In an interview for Jon Bradshaw’s Fast Company, he noted, “It’s the luck factor that seduces everyone into believing that they are good, that they can actually win. But that’s just wishful thinking.” At the height of his success, demonstrating that winning was not due to chance, Holland reportedly earned around $60,000 a year (about half a million dollars today) in prize money and other endorsements.

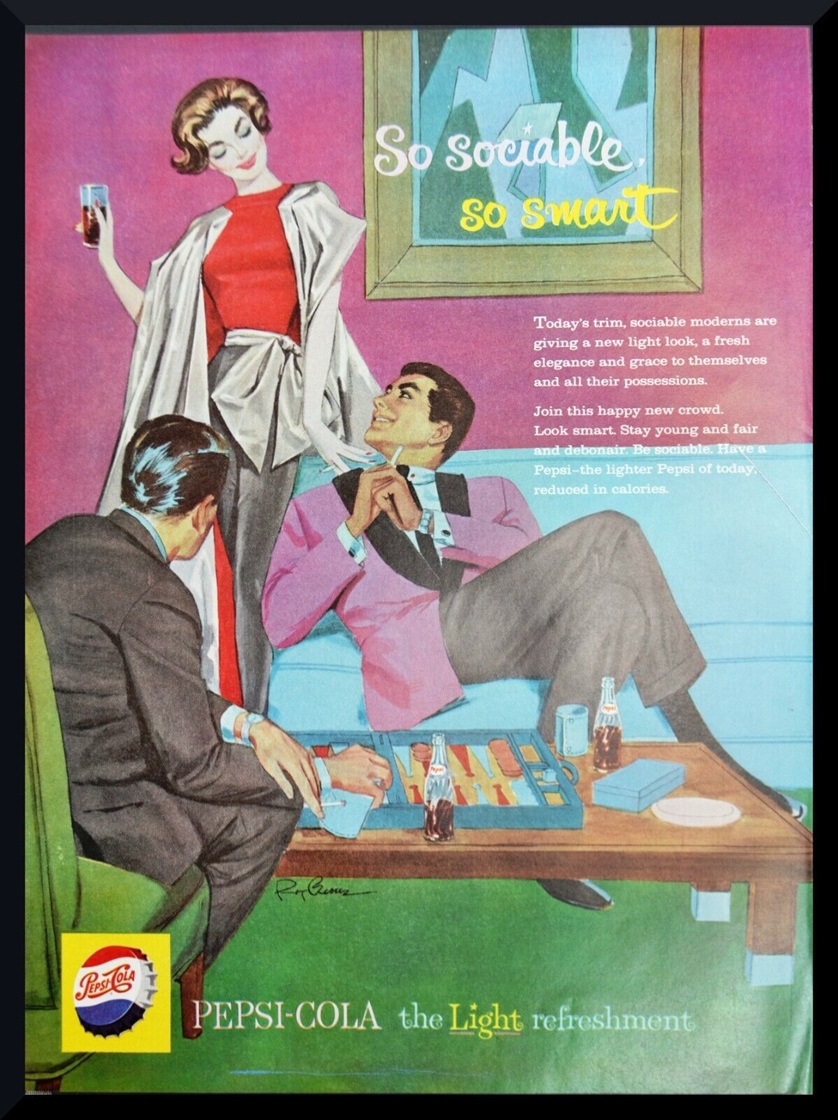

Pepsi-Cola advert from 1959 showing backgammon in the modern home

Legally, the game of backgammon is strategic because everything is known on the board; the position of your counters and your opponents’, and a fair dice have a set number of probabilistic outcomes. Justice Stephen S. Walker, in State of Oregon v. Barr (1982) concluded that, “Backgammon is a game of skill, not a game of chance,” and found the defendant, backgammon tournament director Ted Barr, not guilty of promoting gambling. The state of Oregon had reasoned that, because of the use of dice, it was a game of random chance and, with the offer of prize money, players were therefore gambling.

Tim Holland, showing form as the archetypal sartorially on point lounge lizard, playing as backgammon world champion, circa 1970.

Endorsing the opinion that the game is more strategy than chance, computer scientists have studied backgammon. The implication for the game having a set number of outcomes is that it is amenable to computer programming. With 15 white and 15 black counters and 24 possible positions, backgammon has 18 quintillion (18 million million million) possible legal positions, each with an assigned probability depending on the roll of the dice. With modern computing power, and the use of programmed strategies, a computer can win by brute-force calculation.

And so it did. In 1979, a computer program called BKG 9.8 developed by Hans Berliner, Professor of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University, defeated reigning world champion Luigi Villa, winning 7–1. Paradoxically, Berliner attributed the victory to “largely a matter of luck,” as the computer received more favourable rolls of the dice. Popularity for the game waned in the 1990s, but has since made a comeback through computer play – either against the electronic opponent or with its assistance.

Tina Turner, photographed for Backgammon Magazine, 1979. © Andrea Waller

With the rise of online play against either machine or human opponent, the temptation is to use the same computer programs to cheat. However, this is practically impossible because many online sites use move-comparison software that identifies when a player’s counter positions resemble those of a backgammon program.

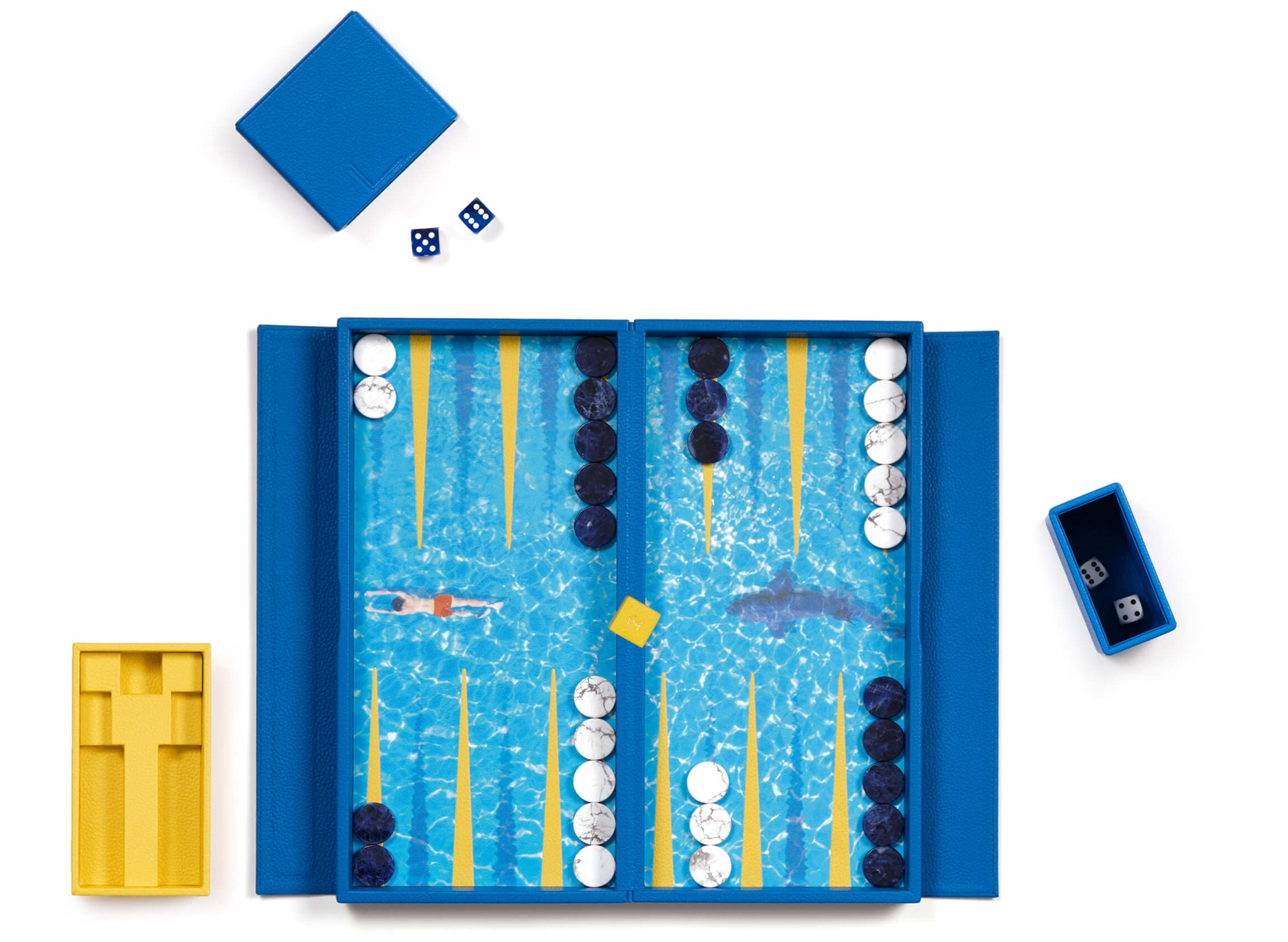

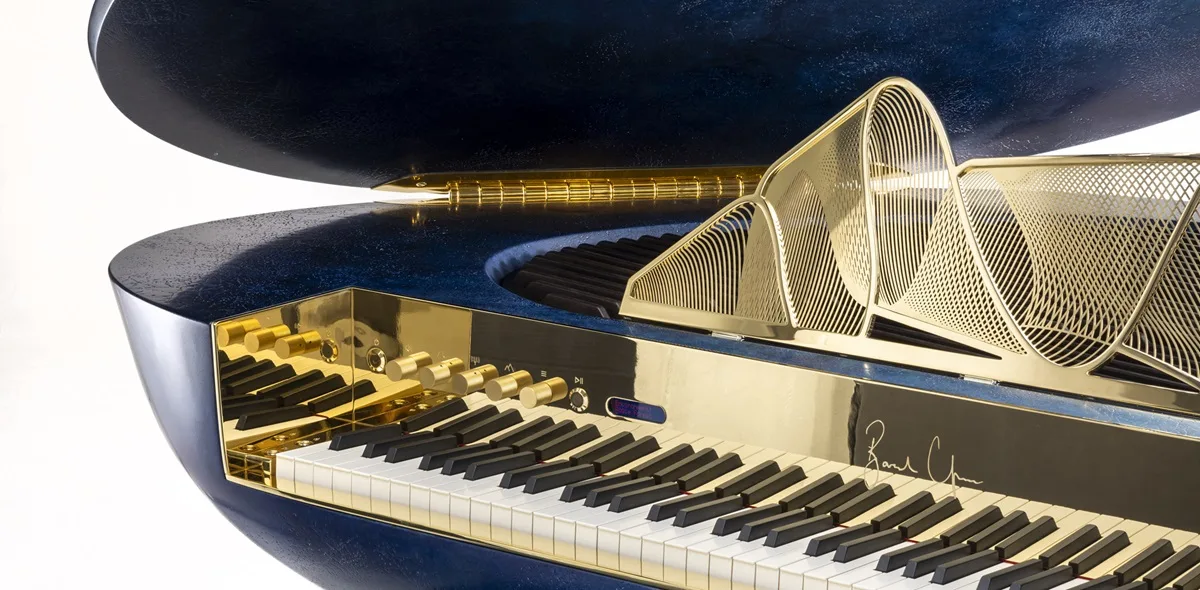

What is obvious from the medieval drawings of the game, through the ages since, is that backgammon should be enjoyed between two people across the board. Perhaps that’s why the game has made a comeback, with sets considered luxury items and prices accordingly. From artisans like Alexandra Llewellyn to megabrands Prada and Chopard, backgammon sets have become practically objets d’art – and are often displayed as such in homes. As a player, though, I can tell you that the wood inlay, the weight and manufacture of the counters, the feel of the dice and the cup all are part of the visceral experience of play.

Swimming pool travel backgammon set by Alexandra Llewellyn

Because of the simplicity of the game, the mixture of strategy and chance, there is nothing more enjoyable than an evening in the company of another, as “two peas in a pod,” playing a game or three, and whether you prevail in the end, companionship and amusement are all that matter. David Hume was probably right; for most of us, the social enjoyment of play, away from the trials and tribulations of the rest of the day, make the game both endearing and enduring.

Words: Dr Andrew Hildreth

Opening picture: Hugh Hefner demonstrating his backgammon prowess to fellow residents of the Playboy Mansion.

Show Comments +