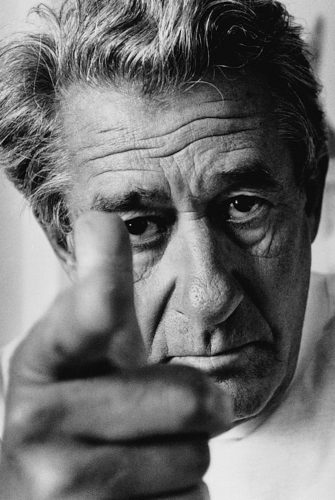

Now that we live in a world seen more often than not through the lens of a smartphone, it’s hard to know what photographer Helmut Newton, who died in 2004, would make of it all. A new retrospective exhibition in A Coruña, Spain, showcases the works of the provocative photographer, underscoring the genius of his enduring, and often erotic, visual art.

A once-in-a-lifetime visual artist, he not only turned the world of fashion photography on its head but also left an artistic legacy that endures to this day. Not bad for a man who once said, “I hate good taste. It’s the worst thing that can happen to a creative person.”

Whether or not you agree is something to be discussed at dinner parties; but his work is considered so important that a major exhibition has been dedicated to his work.

“I hate good taste. It’s the worst thing that can happen to a creative person.”

– Helmut Newton

Helmut Newton – Fact & Fiction has been created with the Helmut Newton Foundation and curated by Philippe Garner, Matthias Harder and Tim Jefferies; it is the third exhibition from the Marta Ortega Pérez (MOP) Foundation.

Known as “the king of kink,” Newton’s provocative photos – many shot in black and white – were ahead of their time. Often featuring sado-masochistic or fetishized images, they sometimes shocked but always entertained.

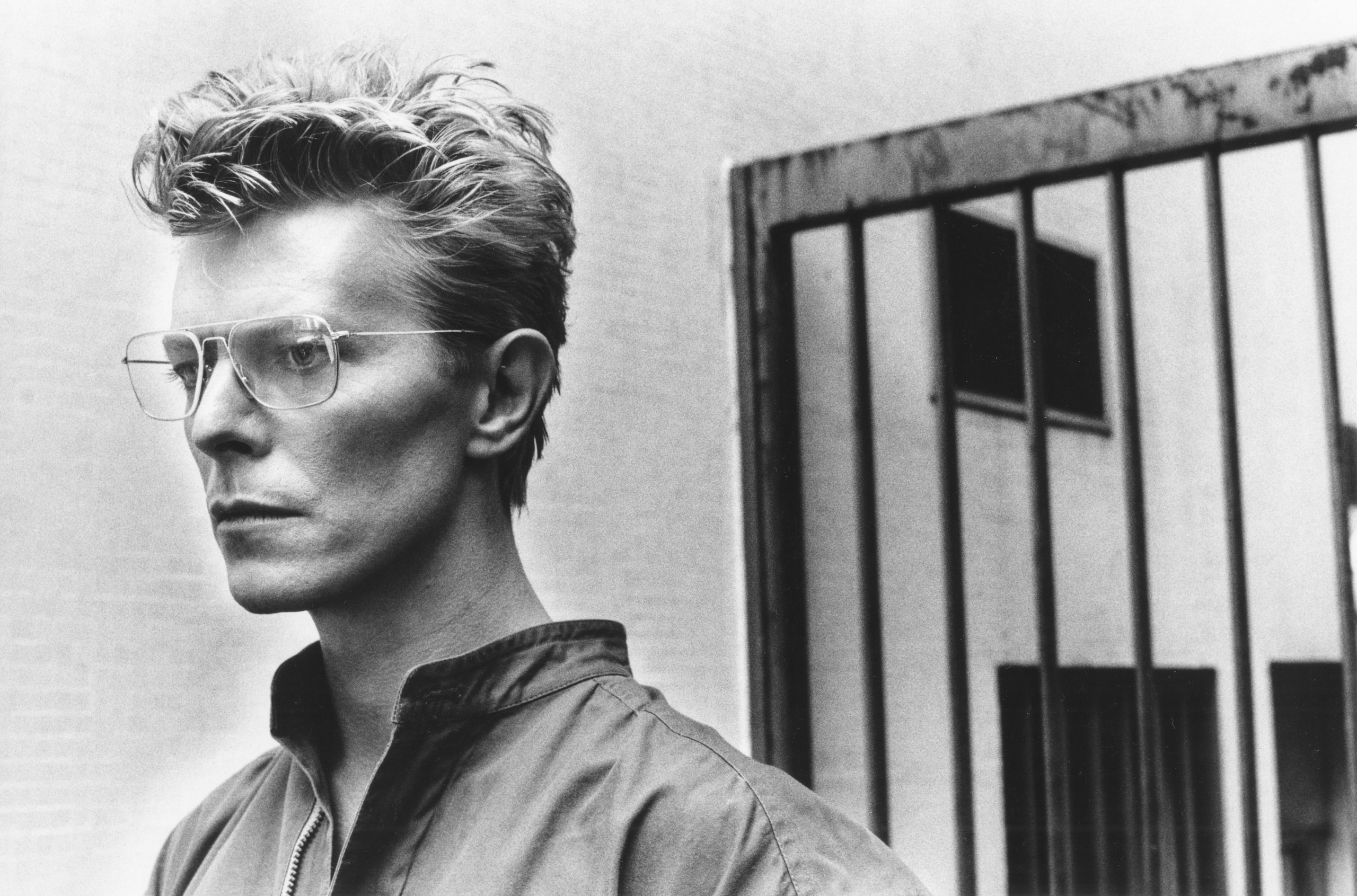

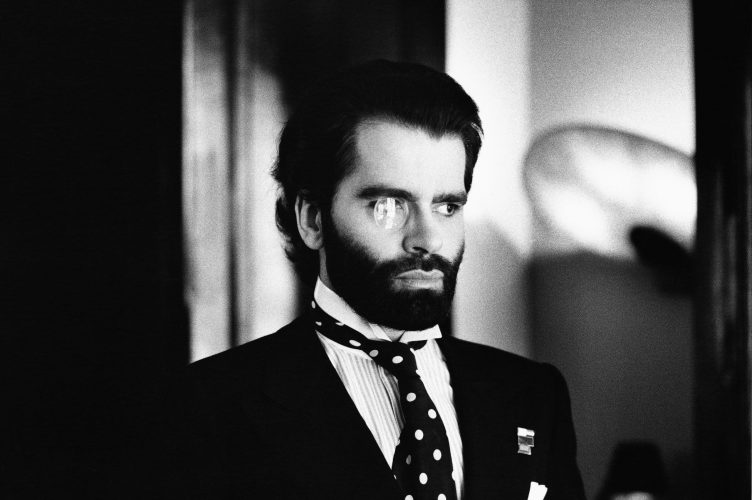

Newton was able to take the most famous faces in the world (and anonymous ones, too) and find new and bold stories to tell. Among those featured in the exhibition are actresses Monica Bellucci, Charlotte Rampling and Daryl Hannah, jewellery designer Elsa Peretti (who modelled Halston’s “Bunny” costume in 1975), Jerry Hall and Naomi Campbell, as well as David Bowie, Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld.

Those who knew him intimately speak highly of not just his incredible eye for an image, and his work ethic, but the way he treated people both in front of and behind the camera.

Helmut Newton, David Bowie, Monte Carlo, 1982.

Stylist Sascha Lilic worked with Newton for more than a decade. Starting his career as a make-up artist and hair stylist, Lilic was introduced to the photographer on a shoot for French magazine Paris Match in Strasbourg, in the early nineties.

“Helmut Newton girls were not supermodels,” Lilic says. “They were women he liked and they didn’t have to be famous, and they didn’t have to be in the pages of Vogue. For Helmut, beauty had many different faces. He didn’t care if they were old or young, and he didn’t care about fashion. He didn’t give it the importance that everybody else gives it. He just wanted a beautiful picture.”

Lilic recalls styling Monica Bellucci with Newton for Vogue Italia at Karl Lagerfeld’s abandoned mansion in Monte Carlo. The standout photo from that 2001 shoot – of Bellucci dabbing her glossy red lipstick with a tissue – is featured in the exhibition.

“… the Kleenex stuck to her lips, and Helmut, who was always looking at what you were doing, screamed, ‘Stop! Take your hands away!’ I did, and he took the picture…”

– Sascha Lilic

That frame was captured by Newton working on instinct. “I wanted red, glossy, shiny lips and Dior had brought out that lip gloss back in the day,” Lilic says. “It was super-sticky, but it looked like Chinese lacquer. Helmut said we had to take it down because it was reflecting back into the light.

“So, I took a Kleenex and tried to block the lipstick down to take the shine away The lipstick was so lush and sticky that the Kleenex stuck to her lips, and Helmut, who was always looking at what you were doing, screamed, ‘Stop! Take your hands away!’ I did, and he took the picture. It was an incredible moment.”

A visionary, Newton’s aesthetic was born out of Nazi oppression and life as an immigrant. Born Helmut Neustädter to a Jewish family in Berlin in 1920, he began taking photos almost as soon as he could hold a camera. In 1936, he became an apprentice to renowned fashion photographer Yva (Elsie Neuländer-Simon), but just two years later was forced to flee his homeland.

He landed in Singapore, where he found work as a photographer at a local newspaper. However, it wasn’t long before he was interned by the authorities and sent to Australia, where he served in the army for five years. On becoming an Australian citizen, in 1946, his name was changed to Helmut Newton.

“Look, I’m not an intellectual – I just take pictures.”

– Helmut Newton

It took 10 years before he landed his first contract for British Vogue, and after that French and Australian Vogue, but by the seventies, his portraits of women in erotic, unconventional and powerfully charged poses had changed the face of fashion photography.

Lilic, whose own family left Yugoslavia for Germany under dictator Tito’s regime, said he bonded with Newton over their early disrupted lives. “We started talking on the day we met about our childhoods and found that we had many things in common. We were both running away from politics. Even though there were two generations between us, we became family. I would often spend time with him and [his wife] June at their home in Monaco.”

It was Newton’s skill at finding extraordinary moments in a way never seen before that propelled him to the top of his profession. While his personal history informed his art, Newton said of his style, “I have always avoided photographing in the studio. A woman does not spend her life sitting or standing in front of a seamless white paper background. Although it makes my life more complicated, I prefer to take my camera out onto the street … places that are out of bounds for photographers have always had a special attraction for me.”

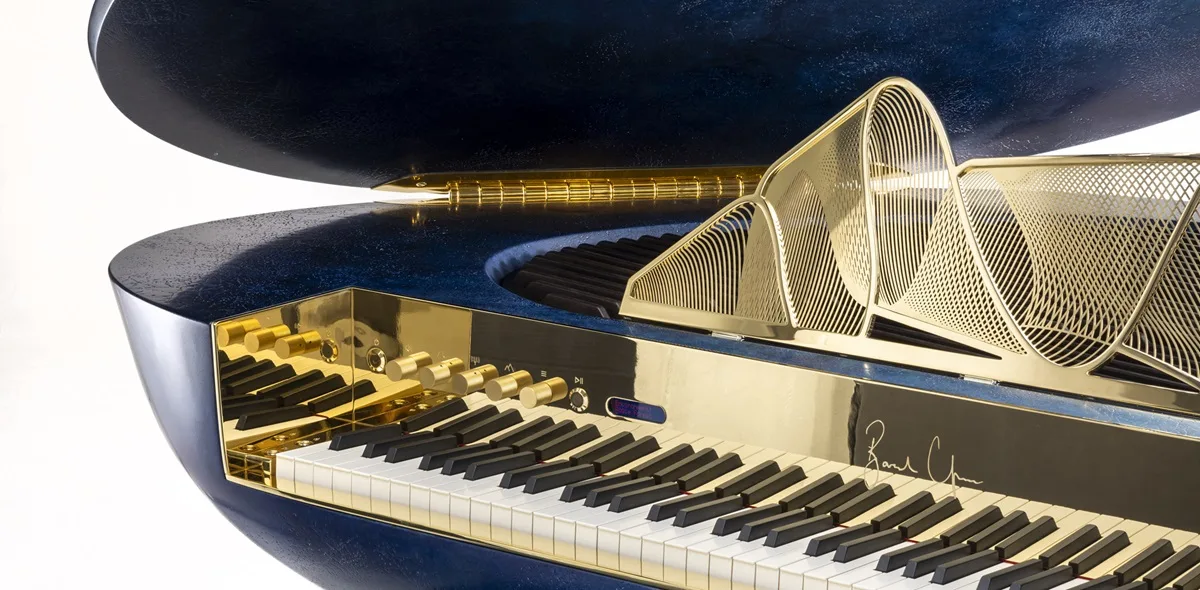

Helmut Newton, Bordighera Details, Italian Vogue, Bordighera, Italy, 1982.

Lilic says he thinks Newton’s artistry was also about giving women control. “He showed how much power women can have over men just by their physicality. I think that’s why it was so different, especially at the time, because nothing like that had been seen.”

Graciously, Newton would always give credit to his wife, June Newton, née Brunell, also known as Alice Springs (after the place of her birth). An actress as well as a gifted photographer in her own right, she met Helmut in 1947 when she posed for him. They were married the following year. “I was lucky to have my wife as the art director – and it turned out to be quite something. A great success. I’m very proud of it,” he once said.

Lilic recalls that on set, Newton would leave to have lunch with June and then return full of ideas. “They would kind of elaborate on a script together. They really did rely on each other.”

Helmut Newton, Karl Lagerfeld, Paris, 1973.

His death was sudden. He had a heart attack driving his car while leaving Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont in January 2004. He was 83. Lilic remembers how shocking it was. “It took me a while to get over it,” he says. “But thinking back, I had something a lot of people will never have and I was very, very lucky to do so. I come from a time of analogue photography, and for 10 years I worked with one of the biggest, if not the biggest, masters of photography that ever lived. That’s something nobody can take away from me.”

We’ll never know if Newton himself would agree with how the world still sees him. He once said, “Look, I’m not an intellectual – I just take pictures.” But what incredible pictures they were.

Helmut Newton – Fact & Fiction

Marta Ortega Pérez Foundation, A Coruña, Spain

18th November to 1st May 2024

Information and tickets, HERE

Words: Lisa Marks

Opening image: Helmut Newton, Grand Hôtel du Cap, Marie Claire, Antibes, 1972, © Helmut Newton Foundation. Image cropped from the original due to format limitations.

Show Comments +