Sister to one of the most famous names in the history of fashion, Catherine Dior was a tower of strength and courage. She joined the French Resistance, was captured and tortured by the Gestapo, suffered the indescribable in concentration camps and escaped a Death March, returning to Paris a changed woman, but never broken.

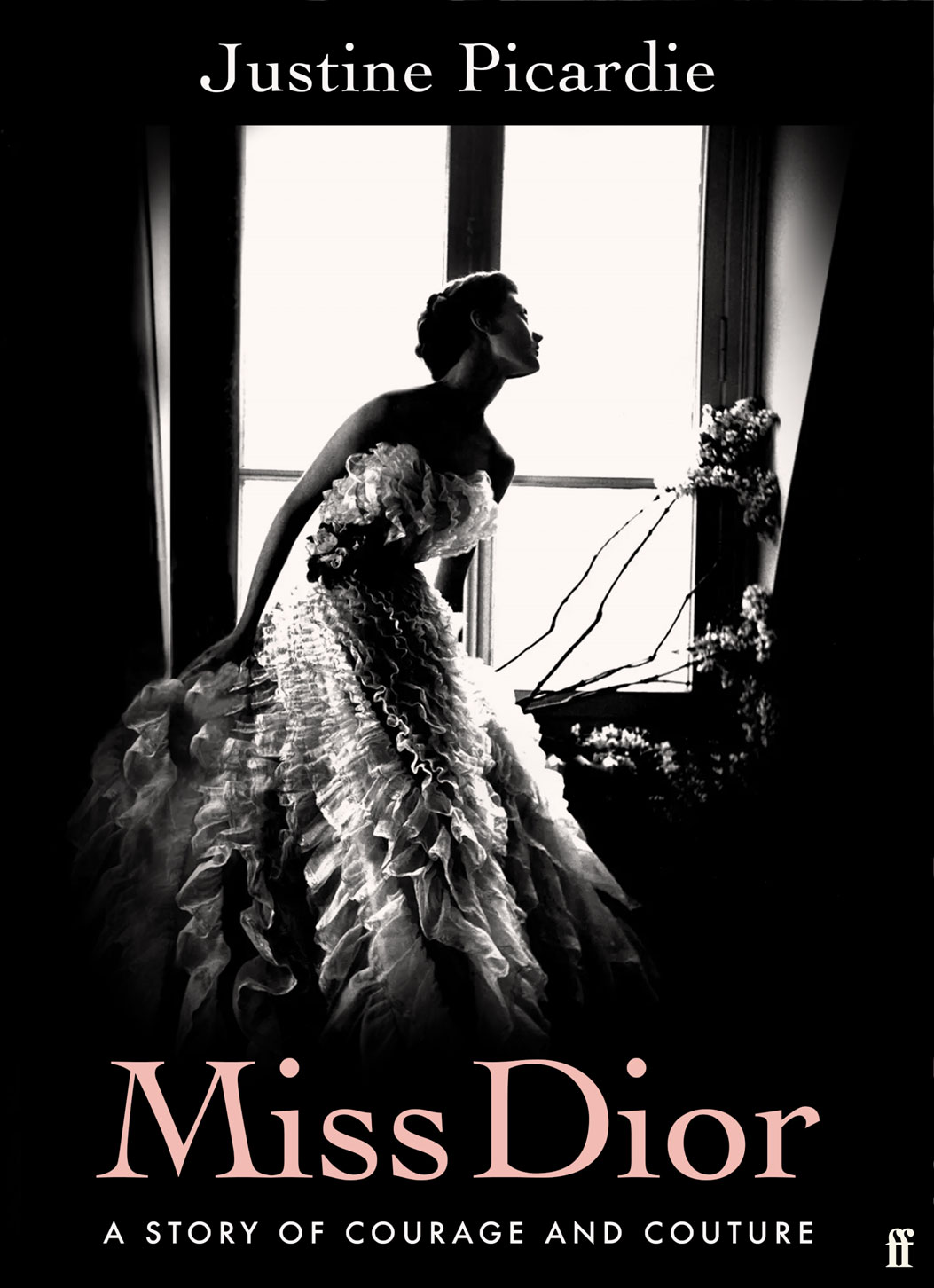

The inspiration behind the legendary fragrance Miss Dior, the story of Catherine is the story of many unsung female heroes who never received the recognition they deserved. Journalist and author Justine Picardie spent over a decade researching her life, which she has painstakingly pieced together in a delightful and unforgettable book that honours not only Catherine Dior, but also the many other courageous women who didn’t hesitate to sacrifice their lives to save their country. Born in 1917, Catherine was the youngest of five children. She lived with her family in Granville, on the coast of Normandy. One of her passions was gardening, and she was particularly fond of roses, a love she inherited from her mother and which she cultivated for her own pleasure and as an essential ingredient in the perfume that her brother would name after her and launch alongside his New Look collection in 1947, becoming an icon in itself. Catherine lived with Christian in Paris in the late 1930s, shared a farm with him during the war in the south of France before joining the Resistance.

She served as honorary president of the museum that opened in 1997 in her childhood home at Granville (Les Rhumbs) from 1999 until her death in 2008, aged 90. The horrors of war would touch Catherine from an early age. One third of France’s male population between the ages of 18 and 27 died in the First World War. Her eldest brother Raymond, was the only member of his platoon to survive, but he suffered severe PTSD for the rest of his life, what the French called at the time crise de tristesse sombre (an attack of dark sorrow). Catherine was only 13 when her mother died, forever changing the dynamics of their family life. Around the same time, her father lost his fortune, so Maurice Dior, his children and their faithful maid Marth Lefebvre ended up moving to a small farmhouse, Les Naÿssès, in Provence in 1935. The house didn’t even have electricity. Catherine was unhappy there. So, a year later she moved with her brother Christian to the Hôtel de Bourgogne in Paris. Christian and Catherine would remain the closest of the Dior siblings, sharing their mutual love for flowers, gardening, art and music.

It was a fellow resident of Hôtel de Bourgogne who introduced Christian to an up-and-coming couture designer, Robert Piguet, who bought some of Christian’s sketches and thus started his career as a freelance fashion designer. Catherine also started earning her own money, selling hats and gloves in a fashion shop. Eventually Christian was offered a full-time job at Piguet’s in 1938, which allowed brother and sister to rent an apartment of their own in Rue Royale. Not soon had they settled into their new found prosperity that war was declared on 3rd September 1939. Christian was called up for military service but luckily saw no action as he was sent to provide farm labour in rural central France whilst Catherine was forced to leave Paris and move back to Les Naÿssès with her father. Christian managed to join them in the summer of 1940 and soon they fell into an acceptable routine. They grew vegetables and sold them twice a week at the local market. However, as the Nazis were requisitioning colossal amounts of French produce, food shortages became more severe, even for the Dior family. In autumn 1941, Christian returned to Paris to look for paid work as a designer but Catherine remained in Callian, where soon after, she’d meet the man who’d change her life forever: a hero of the French Resistance called Hervé des Charbonneries.

Catherine and Hervé met in a radio shop where he was manager. Catherine was looking for a radio to listen to the broadcast of Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French in London. It was love at first sight. However, it was not to be an easy relationship. Hervé was married with three children, he was amember of the Resistance as was his wife Lucie. Hervé was part of a network called F2, which had close contacts with Polish and British Intelligence services. Following the invasion of Poland in September 1939, the Polish Intelligence had moved to Paris, where they got very close to the station chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service, Wilfred Dunderdale, a suave character who legend has it was the inspiration for James Bond, since Dunderdale was friends with Ian Fleming. By the end of 1941, Catherine was dividing her time between Callian and Cannes, where she rented an apartment to be closer to Hervé and the other members of F2, in charge of gathering information about German troops and warships. Records show that by the end of the conflict, F2 had around 2,500 agents, of whom 23 percent were women.

At least 900 of them were interned, deported or killed. A dossier in the military files of the Resistance shows that Catherine played a vital role in the operation of the Cannes office gathering information, compiling intelligence reports and even hiding incriminating materials from the Gestapo during a raid, before delivering them safely to another member of F2. She and her colleagues actually provided vital intelligence for the Allied invasion of France – D-Day – planned for early June 1944. In summer 1944 though, Catherine had to flee Provence so she returned to Paris, to Christian’s apartment. She was being hunted by the Gestapo so by sheltering her sister – and her comrades – Christian was risking his own life. In July that same summer, Catherine ran out of luck and was apprehended by the Gestapo, taken to the infamous 180, Rue de la Pompe in the elegant 16th arrondisement, where she and many other victims suffered terrible forms of torture. Several other women from F2 were arrested at the same time: Anne de Bauffremont, Yvonne de Turenne and Jeanne Van Roey.

– Zahava Szász StesselShe didn’t want to be pitied.

She was the captain of her own soul…

Catherine and her colleagues were beaten, raped and almost killed, as a favourite form of torture by the leader of the Gestapo gang (Berger) was to submerge his victims in icy water for hours, take them to the verge of death and then bring them back. Despite suffering a series of violent assaults, she was not broken. Whichever answers she gave to her captors, she protected her colleagues in the Resistance, saving the lives of many, among them her friend Liliane Dietlin, her lover Hervé, his wife Lucie, and two of the F2 leaders, Gilbert Foury and Stan Lasocki. By the time the Gestapo got to their headquarters, they had all fled. No wonder that the records of the Resistance speak about Catherine’s “exemplary courage” when subjected to “particular odious” forms of torture.

Unfortunately, some of the torturers at Rue de la Pompe were French nationals. The most telling evidence comes from a member of the Resistance who had been interrogated there and scratched on the cellar wall with his nails: “We have been tortured by the French people.” There is very little information left from Catherine’s imprisonment in Fresnes, Paris, but we know that by the time she got there, it was filled with members of the French resistance and agents of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and that the conditions were subhuman. At the end of July, a large group of women were moved from Fresnes to Romainville in the outskirts of Paris before being deported to Germany. Catherine was among those women, as it was the American Virginia d’Albert-Lake, Agnès Humbert and several other female members of the Resistance. By that time, US troops had taken Avranches in Normandy and opened the way to Paris so prisoners at Romainville were hopeful that they may be liberated before being deported to Germany. Christian Dior in the meantime had discovered where his sister was held and was desperate to save her.

Catherine would become associated with the scent of Miss Dior, a parfum launched at the same time as the couture brand in 1946…

Unfortunately none of the above was to happen. On August 15th, the women at Romainville were asked to pack their things. It was time. They were put in buses filled to the rim to get to the train station in Paris, where cattle wagons waited for them, insanitary and with hardly any ventilation. Many fell unconscious, most remained strong. Several witnesses said that as trains pulled out of stations, a proud chorus of La Marseillaise could be heard continuously until it faded in the distance.

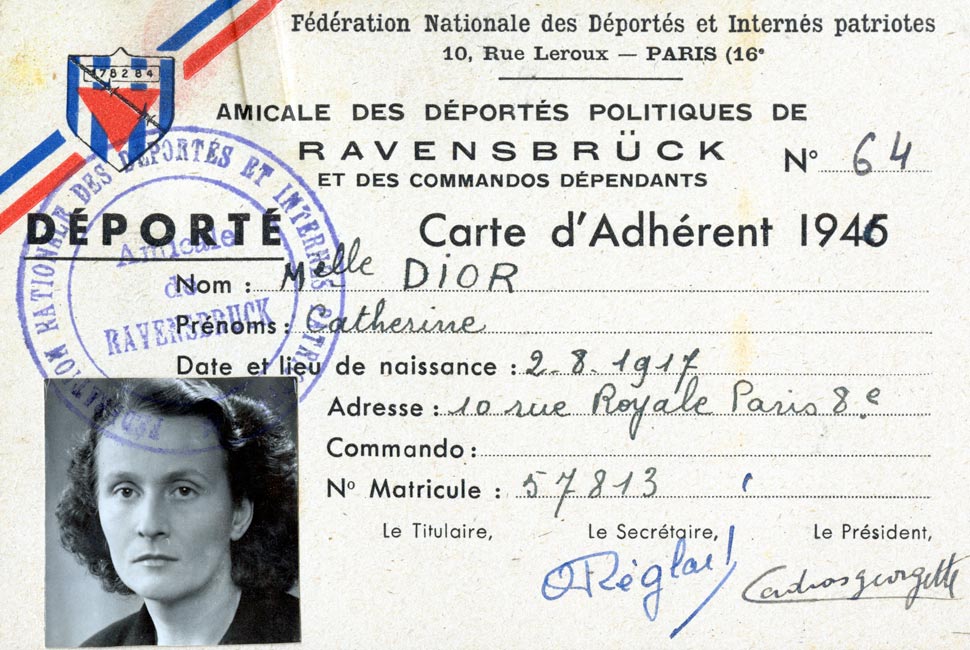

After travelling for a week, Catherine Dior arrived at Ravensbrück concentration camp, the only one intended exclusively for women. Every prisoner was assigned a number according to their date of arrival and alphabetical order. Catherine was number 57813. In total, 22 other women tortured at Rue de la Pompe ended up at Ravensbrück, among them Elisabeth de Rothschild, who had been arrested for refusing to sit next to the wife of the German ambassador at the Schiaparelli show, and who would die there. By the time Catherine arrived, there were already 40,000 prisoners interned. During the six years of existence of this camp, about 130,000 women went through its gates. Estimates tell us that between 30,000 and 90,000 lost their lives while in Ravensbrück. As a memorial site, it never received as much attention as Auschwitz but in 1959, a small area in the camp was opened as a memorial, and several sculptures there symbolise the suffering of the female prisoners. The conditions were inhuman. They were crammed into rat-infested accommodation with hardly any food, rags for clothes and forced to sew a triangle in them coloured according to their category: political prisoners, Jews, asocials… Himmler took a personal interest in Ravensbrück using the women for medical experiments.

Ravensbrück was considered a slave labour camp rather than an extermination one but the truth is that it was “extermination through labour”, as prisoners died by the hundreds of exhaustion, sickness and starvation. Maisie Renault, a survivor of the camp described in her memoir “…Many of our companions are suffering with purulent wounds… Dysentery begins to spread… Even more horrific was the sight of dead bodies lying in the filthy washroom.” Catherine’s godson, Nicolas Crespelle told Justine Picardie that her godmother spoke to him only once about her time at Ravensbrück. Catherine said to Nicolas that she would never fall to the ground to pick up food thrown by an SS guard because “if you did that, your life was over…” That is one of the many things this incredibly strong woman did to not lose her self-respect.

In October 1944, Catherine and another 250 women were taken to another camp, Abteroda. There they worked as slave labour for BMW, building military engines. The conditions were even worse than at Ravensbrück, sleeping on cold cement floors, with nothing but watery soup and dry bread to eat if they were lucky. Still, many of these women,including Catherine, had the courage to sabotage as often as possible the jet components they were being forced to build. As the Allies intensified their bombing campaign against Germany, the Frenchwomen were transferred to another camp near Leipzig, Markkleeberg.

Hervé des Charbonneries and Catherine Dior at their flower stall at Les Halles, 5 rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau, circa 1957. © DR/Collection, Christian Dior Parfums, Paris.

Catherine arrived there in the last week of February 1945. A survivor of the camp, Zahava Szász Stessel, who had worked there since the age of 14 said of Catherine, “She didn’t want to be pitied. She was the captain of her own soul…” Catherine had one single fierce desire: to return to her family home in Provence. So when in April 1945 the Allied forces were approaching Leipzig and the hundreds of thousands of concentration camp prisoners were forced to move towards what was left of Nazi-controlled Germany, Catherine was put into one of these “Death Marches” – so called because one in three prisoners died in them – and managed to escape from it, together with other women who had also been held at Markkleeberg. It was the 21st of April, 1945. In the meantime, Christian had continued to work as a designer in Paris for Lucien Long, and kept desperately looking for his sister. He even employed a clairvoyant. Catherine Dior arrived in Paris at the end of May 1945; her brother met her at the station. Such was her state of emaciation that he did not recognise her at first. Catherine received some of the most prestigious national decorations from several countries: the Croix de Guerre, Croix du Combattant Volontaire de la Résistance, the Polish Cross of Valour, and the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom.

Reunited with Hervé, the couple moved into Christian’s apartment at Rue Royale and sold flowers grown in Provence to florists in Paris, rising at four in the morning to go to the flower market in Les Halles. Her stoicism and determination to rebuild her life were extraordinary. She was also fundamental to the identification of Berger and the other monsters who had tortured her and many of her colleagues at the trial of “Rue de la Pompe Gestapo” at which she testified in 1952.

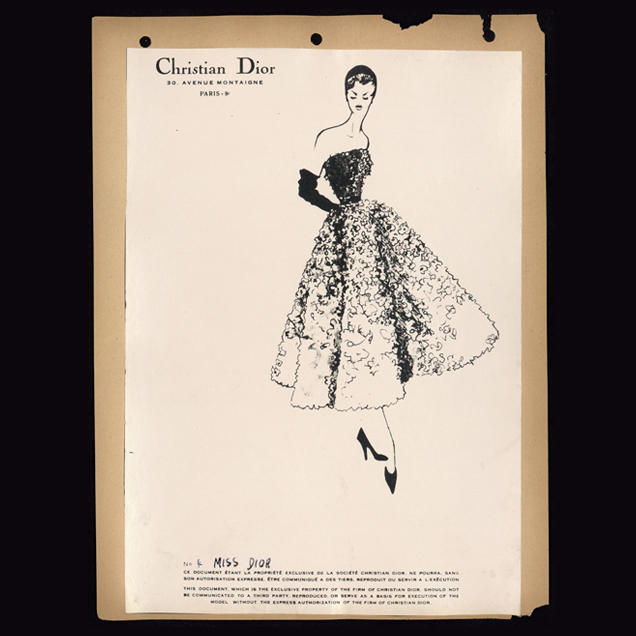

Catherine was recognised a true heroine who exemplified the best and bravest spirit of French resistance during the war. However, she didn’t enjoy being in the limelight so although she worked with her brother and even modelled for his earliest designs, she was not his muse. Her innate modesty and the scars of war probably prevented her from seeking attention. However, Catherine would become associated with the scent of Miss Dior, a parfum launched at the same time as the couture brand in 1946.

Legend has it that Christian was wondering what name to give to his parfum when Catherine walked in and Mizza Bricard (exclaimed, “Tiens! Voilà Miss Dior…

Legend has it that Christian was wondering what name to give to his parfum when Catherine walked in and Mizza Bricard (head of millinery at Dior and muse to Christian) exclaimed, “Tiens! Voilà Miss Dior!” This is how Catherine became the godmother of one of the most famous and delicate fragrances in the world, Miss Dior. Catherine spent the rest of her life with her beloved Hervé until his death, tending to the garden at Les Naÿsses together with the fields of jasmine and roses that would provide key ingredients for the production of Miss Dior. She never boasted about her achievements or her prowess, nor the medals she had been awarded for her courage, including the Légion d’Honneur that she received in 1994. She died in her beloved Callian on the 17th of June 2008, aged 90. In September 2019, Maria Grazia Chiuri, creative director at Christian Dior, dedicated the Spring-Summer 2020 Ready-to-Wear runway collection to Catherine Dior, inspired by her passion for flowers. A fitting homage to a woman who carried her strength inside, a woman quietly beautiful, like a rose in a summer garden.

Show Comments +