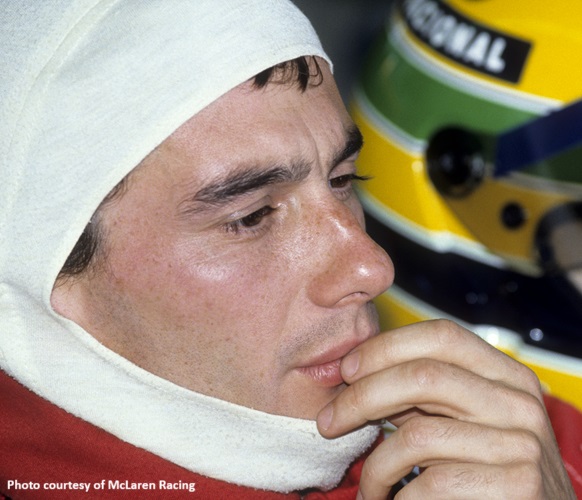

Brazilian Formula One driver Ayrton Senna drove like a man possessed. His rivals feared him, his country worshipped him. When he was killed 30 years ago on live television, he left a legacy of tears, adulation and debate.

At the Monaco Grand Prix, grid position is everything. In 1988, with five minutes of the qualifying session remaining, Ayrton Senna’s McLaren-Honda had recorded the fastest time so far; almost a second quicker than his team-mate, Alain Prost. Even allowing for Prost’s potential to shave a couple of tenths off his own time, it would’ve been enough to guarantee pole for Senna. But this was Monaco, and this was Senna. He was out to prove he was the master and, in the process, psychologically destroy his team-mate. That was just the way he worked. There was only time for one more run. Senna’s McLaren shot through the turns, dancing on the absolute limit of physics. The other F1 cars looked pedestrian in comparison. Senna went a second and a half faster than anyone else had ever lapped the Monaco circuit.

In the history of Formula One racing, no one was better at producing these moments of extrovert brilliance than Ayrton Senna. In May of 1988, he had yet to win the world championship. Indeed, he had only won a mere seven grands prix in four and a half seasons. With Senna, though, it was always about quality rather than quantity.

“If you have God on your side, everything becomes clear.”

– Ayrton Senna

Senna was, in many ways, the first truly professional F1 driver. Like many elite sportspeople, he was a control freak and a paranoiac. But he was also thoughtful and engaging. He was gentle and generous away from the white heat of competition (he gave extensively to charity, usually anonymously), and he also possessed an impish sense of humour that’d reveal itself at his most relaxed.

That said, intensity was never far away, and would only be magnified when Senna left Lotus to join Prost at McLaren in 1988. If Senna were to make an impact, he would have to be measured favourably against the double world champion. This became a fixation that would drive Senna to the kinds of performances seen during that year’s mesmerising Monaco qualifying. But it would also drive him into the wall. That same weekend would prove a startling example. Senna appeared to have the race sewn up when Prost missed a gear at the start and dropped behind a Ferrari to third. The Brazilian pulled away in the lead. By lap three, he was 4.3 seconds in front. By lap five, 7.5 seconds. And so it went on. On lap 54, Prost finally managed to move into second place. Senna was 49 seconds in credit. Not even a driver of Prost’s calibre could hope to make up the difference in the remaining 24 laps. But he had one card left to play: he could mess with Senna’s head.

Ayrton Senna claimed his first World Championship in 1988. Between him and his teammate Alain Prost, they won all 16 Grands Prix that year.

The Frenchman upped his pace and set the fastest lap, knowing that this news would be relayed to his team-mate. As if on cue, for four successive laps Ayrton went quicker still. Then Prost backed off. When that was passed on to Senna, he, too, reduced pace. But the flow had gone. He began to make small mistakes. On lap 67, he brushed a barrier and his McLaren ricocheted into the Armco on the other side of the road. Victory had been thrown away. Worse still, his biggest rival was headed towards the chequered flag. Senna jumped out of the damaged car and walked briskly to his apartment, which happened to be nearby. He shut the door and ignored the phone. He wouldn’t even speak to Jo Ramirez, the McLaren team manager he knew well and respected. “For hours we tried to contact him,” Ramirez says. “His telephone was either engaged or off the hook. At about nine in the evening, I managed to get an answer from his Brazilian housekeeper. At first, she insisted Senhor Ayrton wasn’t there, but I pleaded with her in Portuguese, knowing Ayrton was there. She finally handed the phone over to him – and Ayrton was still crying. “Ayrton,” continues Ramirez, “was a perfectionist. He couldn’t tolerate mistakes by the team, and he tolerated his own even less.”

“Ayrton made so few mistakes that when he did make them, he used to punish himself.”

– Jo Ramirez, former Team Manager, McLaren Racing

Neither could Senna tolerate perceived injustices – and there was none worse in his mind than the events following the 1989 Japanese Grand Prix. Winning his first world title in 1988 hadn’t been enough for Senna; not when he was head-to-head again with Prost the year after. Ayrton – who said the Monaco ’88 accident “brought me closer to God” – was not averse to pushing Prost towards the concrete pitwall at 180mph. Prost would later say: “Ayrton thinks he can’t kill himself because he believes in God.”

In Japan, Prost executed a clumsy blocking move as he tried to defend his lead in the closing stages of the race. Senna recovered from the subsequent collision; Prost did not. But his victory was annulled when officials declared he had broken the rules rejoining the track. It was Prost who won the championship as a result. Senna carried the sense of persecution with him for 12 months, only to have it inflamed at the same track when officials insisted he make his pole-position start for the 1990 race on the dirty side of the grid. Prost, who’d defected to Ferrari but was still Senna’s only real rival, would have the benefit of the clean side. Sure enough, Prost made the better getaway as they rushed down to the first corner at 170 mph – where Senna promptly smashed into the back of the Ferrari, taking both of them out but still winning the title. Senna was not in the least bit apologetic. He’d been messed around with – why could no one else understand this?

This same ethos had driven Senna from the moment he arrived in Europe from his native São Paulo in 1978, aged 18, to race karts. His greatest rival was the British karter Terry Fullerton. “He was obsessed with success,” says Fullerton. “I’ve seen him do silly things when he wasn’t quickest. The kid was loaded with ability, but he didn’t have any fear.”

Senna at the Monaco Grand Prix, 1992, en route to the fifth of his six wins at the principality.

Ayrton reclaimed the F1 title again in 1990 and 1991, but then the wins started to dry up due to the rise of Williams-Renault. Once the incumbent Prost retired at the end of 1993, Senna switched to the reigning champions for the following season. The Rothmans-liveried FW16 was a difficult car, and 25-year-old Michael Schumacher came straight out of the blocks to dominate in a Benetton car that Senna believed to be breaking the technical regulations. Senna spun out of the first two races, while Schumacher romped to victory. The pressure was building when they arrived in Imola, Italy, for Round Three; 1994’s San Marino Grand Prix.

Senna was shocked by a spectacular practice crash involving his friend and countryman Rubens Barrichello. And he was appalled when Austrian rookie Roland Ratzenberger was killed during qualifying. He resigned himself to race the following day, but he appeared distracted… balancing risk versus reward, considering how long was it wise for him to continue?

Leading the San Marino Grand Prix on lap seven, Senna’s Williams inexplicably left the track and hit the wall at the Tamburello corner. The 130-mph impact tore off the right-front wheel and drove it towards the cockpit, though it was part of the car’s broken suspension that dealt the fatal blow when it penetrated the iconic yellow helmet.

Senna famously said, “The danger sensation is exciting. The challenge is to find new dangers.” All who knew him agree he knew no fear.

Senna’s body was flown home with a Brazilian fighter-jet escort. To put this in context for a UK audience, the death of Ayrton hit Brazilians as hard as the death of Diana would Britons a few years later. Mourners turned out in their thousands to see his casket lying in state. The entire country came to a standstill as the funeral cortege made the ten-mile journey to São Paulo’sMorumbi cemetery, with Alain Prost among the pallbearers. A guard of honour fired a salute over the unpretentious grave. Everywhere, people held banners and messages: “Senna obrigado”, “Adeus Senna”, and “Saudade” – a simple but expressive word with no direct translation in English, which connotes a deep longing for something or someone you loved, but is now either lost, gone, or unobtainable forever.

Many words have been written about this man in the three decades since that awful day, May 1st, 1994. None were more telling than his own, spoken to an English journalist he trusted, the late Russell Bulgin, in January 1994. “If I ever happen to have an accident that eventually costs me my life,” Ayrton said, “I hope it is in one go. If I am going to live, I want to live fully, very intensely, because I am an intense person. It would ruin my life if I had to live partially.”

No one who knew him or saw him race, at any stage of his 34 years, could ever accuse Ayrton Senna of that.

Words: Adam Hay-Nicholls

Opening image courtesy of McLaren Racing

Show Comments +