I am sure it will not come as news to you that human activities are threatening life in the world’s oceans. More than 80% of marine pollution comes from land-based activities: oil spills, agricultural pesticides, industrial sewage, even air pollution…All of which contribute to poison the water and deplete oxygen levels, resulting in the death of many marine plants and shellfish.

Global warming is causing coral bleaching and sea levels to rise as well as alterations in ocean composition, threatening many species of marine life that cannot cope with higher temperatures. At the same time, invasive species are proliferating and disrupting the ecological balance of our waters, while overfishing is a serious problem in many parts of the world. Our Editor Julia Pasarón had the chance to interview one of the world’s premier marine biologist, Dr Richard Smith, in the eve of the publication of his book,

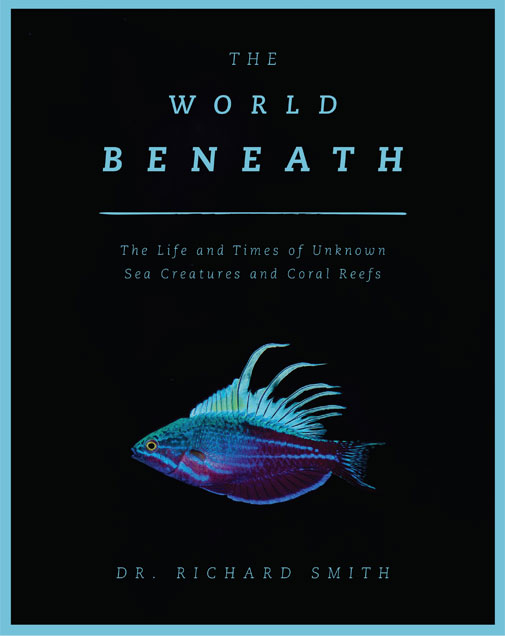

The World Beneath, a richly informative volume that introduces the reader to a myriad of weird and wonderful creatures that most will never have known existed: the polka-dot longnose filefish, the multicoloured seadragon, daffodil crinoids and many more wondrous beings captured in a beautiful collection of photographs taken by Dr Smith over nearly 4,000 dives. Furthermore, the book explains what they eat, how they play and how they care for and live with one another. It also gives compelling insight into which creatures are facing extinction and how we can help before it is too late. Dr Richard Smith first got fascinated by marine life when he learnt to dive with his father at the age of 16.

Some have been on the planet since long before the dinosaurs and we continue to discover many others…

“I studied Zoology in the UK before moving to Australia to pursue and MSc in marine ecology and evolution,” he shares, “I stayed on for my PhD on the biology and conservation of pygmy seahorses. This was the first biological research, beyond their naming, that had been carried out on any of these fishes and showed the fascinating private lives of these diminutive creatures. Spending time working with them on the reef really honed my skills for finding similar-sized creatures and expanded my interest in this realm.”

Richard’s studies show that even the smallest life on earth has captivating social interactions and behaviours. He is a member of the IUCN Seahorse, Pipefish and Seadragon Specialist Group and has taken the only photos ever of a pregnant male pygmy seahorse giving birth. In addition, he recently identified two new species of this tiny animal, the Hippocampus japapigu in 2018, which is the size of a grain of rice and can be found (if you are very lucky) in the temperate waters of Japan and this past May, the H. nalu in South Africa.

Over the years, it is safe to say that Richard has travelled “the seven seas” and right now, he is really worried about the decaying health of our oceans. “Witnessing the change in the oceans is one of the hardest parts of my job,” he says with clear concern in his voice, “some of my first tropical dives happened in the Maldives during 1998, at which time the reefs were being hit by the first global coral bleaching event. As warming waters caused the microscopic algae within the coral’s cells to flee, we witnessed entire reefs turning ghostly white before our eyes. I returned in 2014 and all that remained on many of the reefs was bedrock with a few small coral colonies and algal turf: a shadow of their former glory.” In fact, Richard believes that at this rate of global warming, there may be no coral reefs by 2050; an opinion condoned by UNESCO.

– Dr Richard SmithEvery day, approximately 8 million pieces of plastic find their way into our oceans…

According to the international organization, of the 29 World Heritage reef areas, at least 25 of them will experience twice-per-decade severe bleaching events by 2040 — a frequency that will rapidly kill most corals and prevent their successful reproduction. “Having been fortunate to spend so much time diving on coral reefs and studying their inhabitants, this is obviously devastating,” says Richard, “in my book The World Beneath, I aimed to share some of the amazing diversity found on coral reefs. They are such incredible places that really have no counterpart on land. Many times I have been enveloped by fishes on all sides and it really wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that hundreds of species would be within my reach. Some have been on the planet since long before the dinosaurs and we continue to discover many others. It’s terrifying that all these species are now on such a knife’s edge.”

As threatening as climate change is plastic pollution, which makes 60-90% of all marine debris. Every day, approximately 8 million pieces of plastic find their way into our oceans. It is estimated that there are around 5.25 trillion macro and microplastics floating in the open ocean, weighing up to 269,000 tons. In 2016, a global population of more than 7 billion people produced over 320 million tons of plastic. This is set to double by 2034. The effect of this kind of pollution in ocean life is terrible.

Richard tells us quite a chilling story, “Most people might imagine that one might hope not to see sharks on a dive, but for a marine biologist this couldn’t be further from the truth. The extreme pressure on shark populations from shark finning operations to supply the Asian shark fin soup market has decimated them around the world. Early in my career it was common to see several species around when diving, but the sad reality is that I can now do a two-week trip in Indonesia and see not one shark. However, something I see all too often these days is plastic pollution. Even in the most remote locations, currents can bring great snow-like storms of plastic for as far as the eye can see. It’s no surprise that marine animals mistake these for jellyfish and ingest them.”

Richard has one other sad story to share with us, “One of the most poignant moments I experienced during a recent dive was in a bay in remote northern Papua. Cenderawasih Bay’s secrets were only discovered by scientists in the past couple of decades. In particular, the Cenderawasih Damselfish species was only described in 2012. The unusual geology of the bay has resulted in many endemic reef species found nowhere else on earth. The first time I saw one of these rare fishes, I watched on aghast as it tended to its clutch of eggs laid on the side of a plastic bottle.”

Talking more about his research work and his recent discoveries, Richard comments, “I’ve worked with one of the world’s leading seahorse taxonomists, Graham Short, whose contribution was invaluable to documenting the Hippocampus japapigu. I had observed the Japanese species some years ago, but lacked the highly specific skill set to describe it. Thinking this would be the last new pygmy discovery in a while, I was surprised when I was forwarded an image from Dr Louw Claassens, who was in South Africa on an expedition in search of another new species, a pygmy pipehorse. Bad weather had prevented her from diving, but her presence in Sodwana brought images of the new species out of the woodwork from local divers. Among these images was something she wasn’t expecting: the first pygmy seahorses ever to be recorded in the Indian Ocean, thousands of miles from the nearest pygmy sighting.

This is like finding a kangaroo in Norway! A few months later I joined Louw and finally the Hippocamus nalu was named, after Savannah Nalu Olivier, who first brought this amazing discovery to our attention. Diving with Louw in South Africa, they finally found the new pygmy pipehorse that had originally taken her to Sodwana and they are currently working to name it. Furthermore, Richard announces, “I have also discovered a likely new and stunning dottyback fish from Indonesia that I would love to investigate further.

I have seen so many new species and behavioural observations since writing The World Beneath that I could already fill the pages of another book!” At the pace our ocean life is dying, I am not sure for how much longer there will be anything to write about. Richard seems more optimistic, “I think that the younger generation is trying to educate the older when it comes to pollution and the climate crisis.

They have already seen significant environmental shifts and are frustrated by the political status quo that stymies change.” When asked what is what we should all burn into our brains to help slow down the decay of our oceans, Richard replies, “Keep your footprint as small as possible and make conscious decisions when it comes to food and other consumables. Conservation organizations do amazing work, so supporting them helps us all.”

Instagram – @Dr.RichardSmith

Facebook – @OceanRealmImages

Twitter – @Rich_Underwater

The World Beneath, published by Apollo.

Hardback £26.99. Available on Amazon.

Show Comments +