With a career in land management that covers three and a half decades, you’d struggle to find a man who knows and cares more about working with nature than Jake Fiennes. As Director of Conservation at the Holkham Estate in Norfolk, Jake is working with farmers, gamekeepers, gardeners and even visitors to safeguard the integrity of the estate for the enjoyment of many generations to come.

Jake arrived in Holkham in November 2018 after Lord Leicester offered him a new role on the estate to make it a model of sustainability in the country. He had been managing 5,000 acres in South Norfolk and working with many organisations such as the National Farmers’ Union and the RSPB. He was also on the panel for the National Parks Review, so he was more than ready to take on the challenge. The Holkham Estate comprises 25,000 acres of land, of which 5,000 are in the ownership of Holkham and form part of the National Natural Reserve. This is home to many indigenous plant and animal species and visited by nearly a million people every year. Jake oversees the management of the Natural Reserve and the Game Department and advises the Farming & Forestry Department. “I don’t tell them what to do,” he explains, “I just try to guide them into adopting practices that are environmentally beneficial.” A big part of his job is the implementation of regenerative agricultural practices in as many of the thousands of hectares that make up the farmland of the estate as possible.

People are slowly learning to enjoy nature with respect and put a value to it…

– Jake Fiennes

Regenerative agriculture is a conservation and rehabilitation approach to food and farming systems based on topsoil regeneration, biodiversity and resilience, improving the water cycle, enhancing ecosystem services, supporting carbon capture, and strengthening the health of the soil. Jake rises an eyebrow at my long-winded definition and comments, “In more simple terms, it is about how we can keep producing the food we need, minimising the impact on the environment.” Didn’t I just say that? In his book, Land Healer, How Farming Can Save Britain’s Countryside, Jakes explains how his radical approach to habitat restoration and agricultural work has nurtured the species on the estate and boosted its crop yields – bringing back wetlands, hedgerows, birds and butterflies.

Upon arriving in Holkham, Jake found parts of it were heavily farmed with short rotations and cash crops, with little or no regard for nature or sustainable food production. Jake’s priority was to make more space for nature. “Many of the challenges we have with climate change stem from the loss of species and natural habitats,” he says. Respecting the dynamics of nature, its own hierarchy, is central to Jake’s approach. “When you remove one bit in the natural world, you create a domino effect with potentially terrible consequences. By making space for nature, we help re-establish that hierarchy and improve the intrinsic value of the landscape visually, which is more enjoyable for the million visitors that come to our Nature Reserve every year.”

All measures implemented are carefully recorded so the change can be appreciated. “In just three and a half years we have seen a significant increase in the number and diversity of species, both birds and invertebrates,” Jake says with pride, “small changes have caused big impact, without affecting the farmers’ bottom line.”

None of this can happen without the support of the public. People are slowly learning to enjoy nature with respect and put a value to it, which is always difficult for things you had never had to pay for before. Changing people is difficult, so Jake spends a lot of his time explaining the importance of the measures taken – such as having dogs on the leash at times of bird breeding – so they realise how they too can be part of the solution with just very small actions. Jake is even bringing nature to the car park of the Reserve.

“Many people arrive here after hours of driving, “explains Jake, “their dogs want to run, their kids feel sick… so unless you quickly bring nature to them, they may only experience it through their peripheral vision. From the moment they get here, I want them to engage with nature, may that be because they see a flock of geese flying over their heads, because a butterfly lands on the bonnet of their car or because of a bird they saw on the beach that they had never seen before.”

The farming side of things is slightly less romantic. Some studies estimate that our planet needs to increase the production of food by 70 percent to feed the 9.9 billion of us expected to walk the earth by 2050. “We can start by stop wasting food,” Jake remarks quickly, “and give nature the respite it needs in order to thrive.” There are 570 million farmers in the world, of which 500 million farm less than two hectares. Jake tells me that 60 percent of those farmers operate in areas already affected by climate change and with temperatures expected to increase by more than three degrees, “a huge chunk of the centre of the globe will not be farmable anymore.”

On the other hand, the intensification of agriculture at a global level is having catastrophic effects on natural resources and biodiversity. “We could look at it from a different point of view,” Jake suggests, “since 40 percent of all habitable land is already used in farming, we could actually use it to re-address the balance with nature.” Driving around the estate, Jake explains that this is precisely what several of the farmers at Holkham are doing. “We are giving back hedgerows and hay meadows to nature (97 percent of which have been lost in England), looking at modern technology to breed plants that are resistant to disease and pests, using nature-based solutions to produce food… overall, we are working with the natural world and not against it.”

There are 800 cattle on the estate, serenely grazing the reserve as wildebeest do on the plains of Africa. “Our grass is not high-quality because we don’t use artificial fertilisers or herbicides, so it is not palatable to some of the modern breeds. We have native British animals like the Belted Galloway and South Devon which we mix sometimes with Aberdeen Angus or Hereford to produce an animal with better quality meat. We are trying to mimic the natural world,” explains Jake, “so our priority is high nature value instead of high food-production value. The difficulty is how to increase the food output.”

This is where looking after the soil comes into play. “Soil is what really sustains life. There are millions of living organisms in each square metre. They interact with plants, and these do so with each other, creating a complex ecosystem vital to the survival of everything else. When soil is degraded, our ability to produce high food yields becomes a real challenge.” Part of the solution is the introduction of plants that heal the soil, such as nitrogen-captur- ing legumes, clovers, nettles, dandelions and foxtail, among many others. In turn, these plants are used to feed cattle in winter. I am learning that nothing here goes to waste if Jake can help it.

An example of success is New Barn Farm, run by Jonny Cubitt and his family of fourth-generation farmers. The farm uses regenerative farming practices to grow a wide range of sustainable crops for local outlets within a 15-mile radius. The quality and freshness of the produce is at the heart of the business. Typically, something would be growing in the fields in the morning and served on a plate by lunchtime (which also avoids the loss of many micro-nutrients).

Another family who have been farming here for a long time – exactly 400 years – is the Coke family. James Beamish, now in charge, wants to ensure they continue to do so for another 400 by applying regenerative farming principles. A lot of the beef served at The Victoria – the postcard pretty hotel within the estate – comes from their “conservation-grazed” cattle on the Nature Reserve. The lamb comes from sheep which graze a mixture of grass, legumes and herbs, which, as mentioned above, are planted as a break crop within the arable rotation. They also produce the best malting barley in the country, which supplies the local brewery, Adnams, to make their award-winning beers.

When soil is degraded, our ability to produce high food yields becomes a real challenge…

– Jake Fiennes

The stunning coastal landscape, magnificent stately home, rolling parkland and many attractions and events, make Holkham a wonderful place to visit. Photo © Henri Lart.

Complementing the husbandry side of the estate is the Game Department. Shooting has always been common on large rural estates in Britain and Holkham is no different. “They produce sport for guests – which means revenue – and they help us control the deer population, which are a big problem, as are muntjacs, which graze at the level at which nightingales nest,” comments Jake. “Furthermore, a lot of the meat ends up in local butchers or pubs.” Supplying supermarkets is more difficult, the reason is the same that we hear from farmers all over the country, “Supermarkets want everything a certain size, certain look… they don’t want what they call ‘ugly food’, but nature doesn’t work like that.”

It is the same with fields. The medieval breakdown of farm fields doesn’t work with modern machinery, an obstacle that Jake is turning to his advantage. Showing me a few misshapen fields, he points at the parts where the machines can’t get and says proudly, “Farmers think in straight lines because of their machines, so the bits that fall out are the ones we give back to nature. We plant different plants and flowers that capture atmospheric nutrients so don’t need fertilisers, encourage pollinators and insects to feed the birds and we stopped cutting back hedgerows, which are a very important source of food for birds in winter and a habitat for many species, such as the yellowhammer, which only nests at certain height.” The population of this pretty little bird had gone down by 80 percent in the last 70 years but at Holkham it has doubled in the last two. Even bee numbers are growing, with beehives kept in several parts of the estate.

Language, Jake tells me, is fundamental to get farmers on his side. “Instead of calling them hay meadows, I call them forage for livestock, which makes them technically part of the food system. The fact that I have helped make the use of machinery more efficient also gets me positive points with them,” he adds grinning. He gets even more thanks for his succinct approach. “I let them decide. I ask them just to let me know which fields and which bits they are going to leave out for me to do something with them.” As an example, Jake points at an uneven, irregular-shaped field with nine corners, a spring in the middle and an archaeological burial ground underneath. The book definition of uneconomical. “We turned this field to nature and let her do her magic: the soil feeds the plants, plants feed insects, insects feed birds, birds and insects pollinate plants, etc.” This is one of those small actions Jakes mentions all the time, with a big impact in combating the degradation of species and habitats. An extra benefit of leaving the soil alone is the reduction in the release of CO2, which happens when it is disturbed.

Keeping these high standards on the estate is not cheap. Holkham receives some grants and subsidies from the Government and other organisations and gets revenue from visitors and agricultural rents. Other estates in the country are following suit but this is not enough for the change that needs to be seen soon if we are to secure the future of our beautiful planet. Also, it is not enough to take care of what we do here. The damage caused by intensive farming in other parts of the world affect us too, so Jake points out that, “when we import food produced at lower environmental and welfare standards, we are just exporting our degradation.”

The population of this pretty little bird had gone down by 80 percent in the last 70 years but at Holkham it has doubled…

– Jake Fiennes

At a larger scale, there is a need for governments to put in place legal and economic policy frameworks that encourage global corporations to come onboard the train of sustainability. As Jake says, “Governments have billions, but those companies have trillions.” Referencing the Paris Climate Accords of 2015, he adds, “We only have seven years until 2030.” Before leaving, I pay a visit to Mark Morrell, in charge of the Walled Garden at Holkham Hall, to see other efforts made on the estate to make it self-sufficient. As we are in the middle of spring, the garden is a beehive of activity. There are gardeners everywhere carrying pots, pushing wheelbarrows, inspecting plants… Mark starts by explaining that a lot of what I see is being made possible by the £726,000 in grants they received over the last three years from the Cultural Recovery Fund, the Historic Houses Foundation and Historic England. The estate itself has spent around £1million on the Walled Garden project.

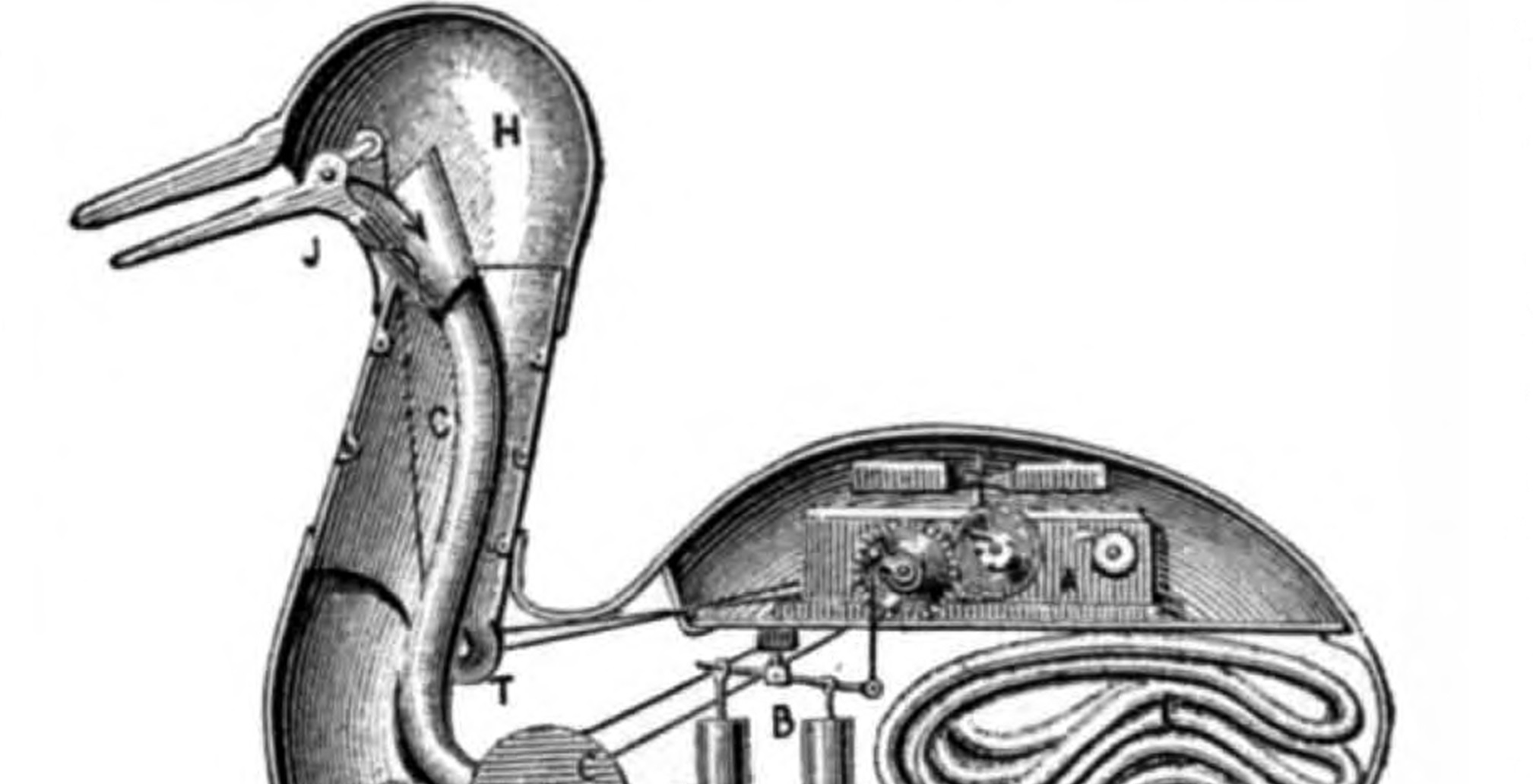

Designed by the neoclassic architect and engineer Samuel Wyatt, the Walled Garden dates back to 1780 and covers six and a half acres. A primary example of Georgian glass house and garden, it was originally built much closer to the main hall, but Mark explains that, as it was a “dirty” working area, it was moved further afield, to its current location (just 10-minute walk from the main building).

In Georgian times it was very popular among the upper classes to cultivate pine- apples, melons and all kinds of exotic fruits to show off their wealth. It was the Dutch who, in the 17th century, started the trend and by the 18th century it has moved across to Britain. “Actually Scotland pioneered the use of glasshouses in Britain,” shares Mark, “and the practice gradually forced its way down through the rest of the country.” It was also the dawn of the industrial revolution, so new technologies were starting to be applied to horticulture as well as the introduction of foreign plants.

The Walled Garden dates back to 1780 and was designed by architect and engineer Samuel Wyatt. Photo © Henri Lart.

For nearly two centuries, the gardens at Holkham were responsible for the production of fruit and vegetable for the hall. Any surplus was sent to London markets by train. “We don’t do that anymore,” Mark explains, “but we still supply the hall and the nearby The Victoria. We grow squashes, tomatoes, chillies, salad leaves, carrots, brassicas, pears, apples, lemons…” As we move to another glasshouse, he points at what I think is a camellia and says, “This is my latest project, tea.”

As we leave the greenhouses area, he shows me different gardens bursting with seasonal herbs and all kind of vegetables and fruits, including one with vines. They haven’t yet perfected the art of viniculture but this year they are getting their grapes pressed by a different winery. “It is still a work in progress, we haven’t given up yet,” says Mark with enthusiasm. I must admit I am very impressed with what Jake and Mark have shown me. It is testimony to Lord Leicester’s intention to safeguard the estate for the future and the commitment of all the people that work here and that share his view of a sustainable future. As I start making my way back to London, I reflect on the many reasons Jake and all the other everyday eco-warriors connected to Holkham have to be proud of. The degradation of the soil has slowed down and even turned around in certain areas of the estate, sustainable food production is growing in the farms and in the gardens, as it is the number and variety of animals and insects that now enjoy living in Holkham.

Show Comments +