In August 2021, our Adventure Correspondent Hugh Francis Anderson embarked on an audacious journey to recreate a Polar expedition on its centenary, alongside discovering more about the changing Arctic.

While researching in the Royal Geographical Society in early 2020, I stumbled across the March 1922 issue of The Geographical Journal, where I found the original report from the August 1921 British expedition to the remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen. The island was immediately familiar – Norwegian Andreas B. Heide, with whom I have worked extensively on scientific communication stories and expeditions, sailed there once in 2012 onboard his research vessel Barba and subsequently told me about the voyage. I first wrote about Barba for this magazine in 2019 after the Arctic Whale expedition to study the effects of microplastic on the marine mammal population in the waters surrounding Iceland. And so, I read the Jan Mayen report with interest and discovered that the expedition was led by Sir James Mann Wordie, who achieved fame as the geologist and chief of scientific staff aboard Endurance during Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Arctic Expedition, 1914-1917. Wordie’s Jan Mayen expedition aimed to undertake the island’s first geological study and claim the first ascent of the world’s northernmost volcano, Mount Beerenberg. A brief call to Heide and an anniversary expedition were born.

Satellite image of Mount Beerenberg, which rises two km out of the ocean. Note the number of crevasses.

The island of Jan Mayen is a seldom-visited, hostile place. With a landmass of just 377km2, it lies between Greenland and Norwegian Seas and sits alone in over two million km2 of open ocean. Its north is dominated by the glacier-covered Mount Beerenberg, which rises over two kilometres out of the ocean. Our journey to Jan Mayen formed a key chapter of Barba’s wider Arctic Sense expedition, a collaborative four-month, 3,000 nautical-mile scientific communication and storytelling voyage to the polar Atlantic with a rotating team of scientists and storytellers. In our chapter, we sailed over 1,200 nautical miles from Svalbard, across the Greenland and Norwegian Seas to Jan Mayen, and further on to the Shetland Islands, arriving in London some five weeks later. In a modern interpretation of a 100-year-old expedition, our goals were threefold: to conduct further marine research, summit Mount Beerenberg, and collect glacier samples. In doing so, we aimed to expound a previously untold tale of polar exploration alongside collecting data to help inform scientists about a rapidly changing Arctic.

Heide and his team were able to observe two fin whales while they were feeding on a school of fish

Life Underwater

“Marine research has a great importance for the general life support function of the ocean, and for using the ocean in a sustainable way to feed an ever-growing population,” says Heide. “In the Arctic, it is of special importance as the ecosystem is undergoing rapid change with retreating ice as a result of global warming. The retreating ice also brings with it an increased opportunity for commercial exploitation of the region, making it even more relevant to document what we are at risk to lose.” In partnership with the research group Whale Wise, and with the support of the University of Stavanger and the University of Iceland, a comprehensive research plan was established to gather as much information on the Arctic and sub-Arctic cetaceans as possible. “Our aim was to monitor Arctic ecosystems, focusing on whales, in an unobtrusive way. In other words, we wanted to provide an Arctic Sense,” says Whale Wise cofounder Tom Grove. “Due to its innate hostility, Arctic ecosystems remain poorly characterised. Across large parts of the Arctic Sense route, the occurrence, distribution, and diversity of cetaceans are virtually unknown.”

Our journey to Jan Mayen formed a key chapter of Barba’s wider Arctic Sense expedition,

As we sailed across the Norwegian and Greenland Seas towards Jan Mayen, we passed over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the seafloor plummets from 200m to over 2000m. At many locations along its 16,000km length, it is a hotspot for cetaceans. Yet here in the Arctic, research into deep-diving whales is sparse. Heide, therefore, deployed a towed hydrophone off the stern to record and detect cetacean vocalisations. “To make use of the vast spatial coverage provided by the expedition route, a towed array of four hydrophones – two low-frequency and two high-frequency, was deployed so that we could record vocalisation from the lowest baleen whale moans and grunts to ultrasonic odontocete clicks,” says Whale Wise co-founder Alyssa Stoller. “These hydrophones were interfaced to PAMGuard, a software that facilitates storage of sound files and real-time detection of cetaceans.” Connected to an amplifier and then to a computer with a spectrogram (to visualise vocal recordings), Heide observes the signals from the saloon and detects sperm whales in the depths below. For 48 hours, the towed hydrophone remained in place and was once again utilised around Jan Mayen, recording data from a seldom explored region of the North Atlantic. These recordings are currently being processed by the Whale Wise team.

Visual observations were recorded too and included white-beaked dolphins, walruses, and the world’s second-largest whale, the fin whale. As many as 20 fin whales were observed around Barba as we sailed south from Svalbard. With his expertise as a freediver, Heide entered the water to better understand their behaviour. “By studying the behaviour of the fin whales, a combination of luck and experience gave us the opportunity to study one, and then two individuals, while they were feeding on a school of fish.” This encounter, recorded and later analysed by the Whale Wise team, offered invaluable data. “Whilst the use of bubbles during foraging has been documented for fin whales, few descriptions of feeding behaviours of this species exist in the scientific literature, particularly those from underwater observations,” notes Stoller. “As such, any description of underwater behaviour improves our understanding of fin whale ecology.”

A Changing Mountain

With the centenary climb on our minds from the outset, two questions were raised. Firstly, due to climate change and glacier degradation, would it still be possible to summit using the 1921 route? And secondly, could we collect glaciological data for analysis?

Hugh Francis Anderson and Andreas B. Heide on their climb to the zenith of Mount Beerenberg

I utilised Wordie’s written observations of the original ascent and carefully mapped these into a trackable route using 3D mapping software. With contemporary satellite images provided by Planet Labs, we were then able to better understand the state of the glaciers from a remote location. With crevasses towards the top section of South Glacier as wide as 10 meters, we quickly realised summiting using the original route would be highly unlikely. This was later confirmed through visual observations once on the island. As such, a secondary route proposed by Wordie following the southwest buttress was chosen, and it was using this route that we successfully reached the summit on the centenary of the first ascent. In doing so, we highlighted the visual observations of climate change; the degradation of the glacier was such that we were not able to summit following the original route. Whilst deflated, this came as little surprise. Globally, glaciers are losing over 30 per cent more ice and snow per year compared to 15 years ago, with human-caused climate change widely believed to be the primary reason. However, we also wanted to determine whether other elements were contributing to Mount Beerenberg’s glacial melt.

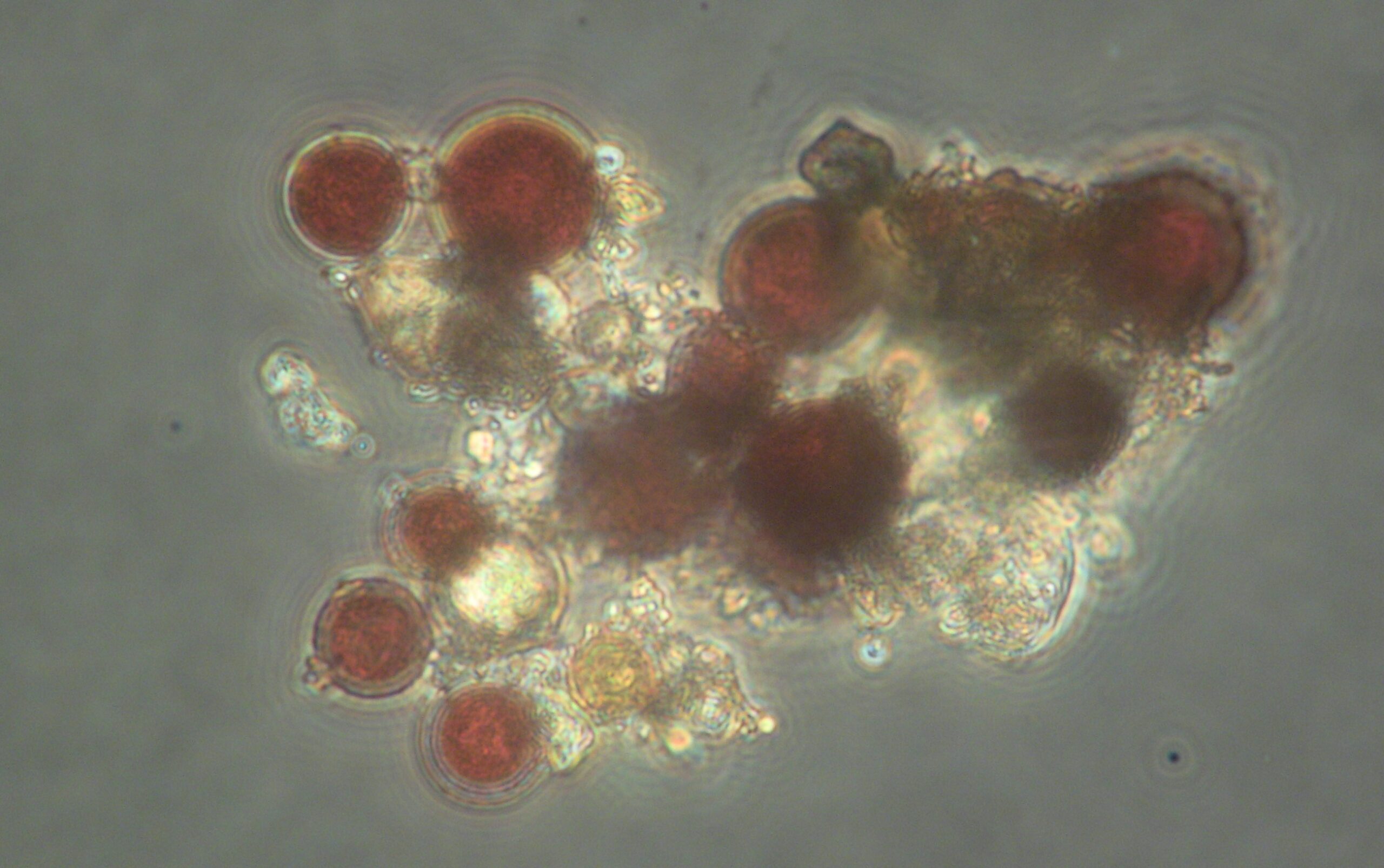

Red snow algae from South Glacier of Jan Mayen under the microscope. Courtesy of Prof. Alexandre Anesio & the Deep Purple project.

Biological darkening is one such cause, and the Deep Purple research project aims to discover more about the growth and origins of algal blooms in the Dark Zone of the Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS). Due to the darkened pigmentation of snow and ice algae, these blooms absorb solar radiation, which subsequently causes them to melt at an increased rate. On South Glacier, we witnessed vast numbers of coloured patches, which we believed to be snow and glacier ice algae. At a selection of elevations, we collected samples for testing by the Deep Purple team. These have now been examined by Professor Alexandre Anesio, one of the project’s principal investigators. With samples analysed under the microscope, Anesio discovered a large number of red snow algae, alongside green snow algae, cryoconite material, cyanobacteria and flagellates. But what surprised him most was the lack of ice algae. “Very interestingly, I could not see any ice algae in any of the samples,” he says. “But, because of the biomass of snow algae that you have in some of the samples, that is going to melt some of the snow, expose the bare ice, which will then be colonised by the ice algae, and which is then going to generate the further darkening of the ice. These samples are important because it just shows how widespread the colonisation of snow algae is across different glaciers worldwide.” The abundance of snow algae, therefore, indicates a noticeable contribution to glacial melt.

The team. From the left: Filmmaker Hugo Pettit, sailor Jaap van Rijckevorsel, the author, sailor Annik Falch and Captain Andreas B. Heide.

In creating a modern interpretation of a 100-year-old expedition, our aim was to use storytelling to share a previously untold tale of exploration alongside utilising civilian science to help scientists and researchers better understand remote regions of the Arctic. In doing so, we also aimed to highlight the importance of adventure, and the need to sate our own curiosity for what lies beyond the horizon.

The Jan Mayen team are currently fundraising to complete a documentary chronicling their journey and research.

www.barba.com

www.hughfrancisanderson.com

Opening picture: Mount Beerenberg ©Hugo Pettit

Show Comments +