Woeful and prophetic tales from the great recession of 1706.

In the Bank of England’s May published monthly briefing, they announced that the current recession we face in the light of COVID-19 might be the largest since 1706. It will potentially be greater than the last financial crisis in 2008, the OPEC oil price shock in 1973, the 1929 depression and the credit crisis of 1772. History and mother nature for that matter, have a nasty habit of reminding all of us every now and then, just how insignificant we are in the big scheme of things. For example, while most of us have settled into the warmth and glow of sitting at home on bounce back loans and furloughed money, the financial implications of a Government imposed war on COVID-19 have seen the economy in free fall.

As new as this may seem to all of us, this is not the first time we face such a downturn in economic fortunes. Back in 1706, England’s economy was hit by a crisis the likes of which had not been known before and led to the creation of the modern state as we currently know it, including the creation of the Office of Prime Minister. There are certain historic threads, acting as cosmic superstring, that reappear in this latest recession as they did then: a questionable and potentially unnecessary war, a divided nation arguing over our role in Europe, a denuded economic base, a new payment system, new infrastructure -and with it a new way of committing crime, over speculation in finance markets and a new approach to the governance of the realm.

Before we look at 1706 and its aftermath, keep in mind that this year we have a war on COVID-19, Brexit has just happened, an over reliance on one single industry (finance), the move to a cashless society and e-payments, private implementation of 5G leading to further cybercrime, the continued proliferation of financial instruments and the sweeping new Government powers enacted under the Coronavirus Act 2020. If the aftermath of the 1706 recession is anything to go by, we’re f%*&ed for some time to come!

The English economy was certainly different at the turn of the 18th century. It was an agrarian economy – pre-Industrial Revolution – and economic activity was dominated by basic needs and food production, which made output more sensitive to the weather. It was not so much what happened that year but the events after that made the recession a notable one.

Recessions tend to accentuate and accelerate trends and forces that are already emerging in the social, economic and political landscape. England at that time was a divided country (between Whigs and Tories) squabbling about Europe, politics, money and taxes. Embroiled in the war of the Spanish Succession, England took part in three battles, which, coupled with a poor harvest, meant it was a costly year. England’s treasury coffers were empty by the end of it with consequent knock-on effects in the economy.

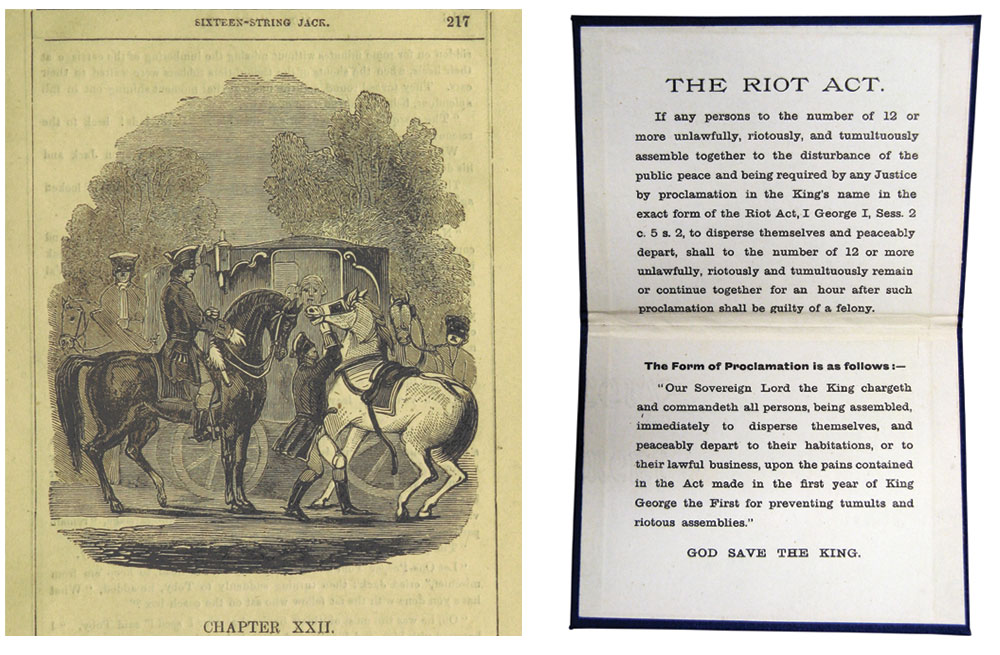

Right: The script to be read to the illiterate populace as The Riot Act (1714).

One of them manifested in the first of the Turnpike Trusts being set up by Act of Parliament in 1707. Because of the paucity of local and national financing for the infrastructure system, it was necessary to invite private investment to fund improved roads. Local communities resented the toll gates and the necessity to pay for the transport of goods and people. In north Wales, this resentment culminated in the Rebecca Riots. One of the other associated social ills was the rise of the highwayman, the kind that would stop the stagecoach, nose and mouth covered by a mask and declare “Stand and deliver!” Stagecoach companies with paying passengers favoured the better maintained highway system administered by a turnpike trust. Highwaymen knew where to look.

Other crime was not so obvious. Debasing the coinage of the realm was both an economic issue and an act of treason. The Bank of England had only been recently founded (1694) by Charles Montagu, first Earl of Halifax. Proving that the “old boy network” was alive and well in the 18th century, with his friend and fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge: Sir Isaac Newton, a new system of payment was introduced; one that lead to individuals being prosecuted for debasing coinage and tying silver and gold currency into a set ratio of exchange. Newton had resigned as an MP in 1701 to devote all his time to stabilizing the medium of exchange within the economy. By controlling the coinage Newton managed to control the money in circulation and with it, an orderly system of receipts and payments for goods and services.

and decrepit.

The debt from the war had other implications on the conduct of government and measures taken to recover revenue. The South Sea Company was a British joint-stock company founded in 1711, created as a public-private partnership to consolidate and reduce the cost of the national debt. As England was involved in the War of the Spanish Succession there was no realistic prospect that trade would take place with areas of the world controlled by the French or the Spanish and the Company never realised any significant profit from the monopoly it had been granted. Despite the lack of profit, the Company stock rose greatly in value as it expanded its operations dealing in government debt, peaking in 1720, before collapsing. The economic bubble had ruined thousands of investors and led to the creation of the Bubble Act of 1720, which determined new rules for setting up a limited stock company.

New taxes were implemented. The Stamp Act of 1712 was passed, imposing a tax on publishers, particularly of newspapers; however, the tax was implemented on a wider basis and covered all manner of publications: pamphlets, legal documents, commercial bills, advertisements, and other papers. The extent of the tax was such that it not only helped partially fill the depleted revenues at HM Treasury, but also helped towards the decline of English literature critical of the government during the period.

Politically, England in 1706 was still tied to the monarchy as a system of governance. The position of Prime Minister evolved slowly and organically through political developments and accidents of history. However, it was the constitutional changes that occurred during the Revolutionary Settlement (1688 – 1720) and the resulting shift of political power from the Sovereign to Parliament that established the office of a “prime minister”. The Revolutionary Settlement gave the Commons control over finances and legislation and changed the relationship between the Executive and the Legislature. Treasury officials and other department heads were drawn into Parliament serving as liaisons with the sovereign. Although the king was not stripped of the ancient prerogative powers and legally remained the head of government, politically it gradually became necessary for him or her to govern through a prime minister who could command a majority in Parliament. But over this time, the power shifted and a new form of government came into being.

After a succession of poor harvests and consequently, several recessionary years, the populous was becoming tired of the various measures implemented to increase tax and control spending. Riots had occurred over the years since 1706 causing the Government to enact the Riot Act in 1714. It was an act of Parliament which authorised local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and to disperse or face punitive action which was summed up in the legislation’s official title: “An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters.”

It was not repealed until 1967. However, in a strange twist of the historic threads, Schedule 22 of the Coronavirus Act 2020 contains a section that allows the Secretary of State powers over all events, gatherings and premises. Equally, with the continued poor weather -the great frost of 1709 iced the economy for a second time in five years, came the first glimmer of change to a new economy. In Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, Abraham Darby I successfully produced cast iron using coke fuel in his blast furnace. In time, because of the lower economic cost of producing it, cast iron replaced wrought iron and with it, the seeds of new economic growth from the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the eighteenth century were sown.

If we are to learn from history, the moral of the story is to beware of new announcements in the future. If this is a prophetic tale, then there will be a brave new world of public-private debt, business will have to be conducted with individuals wearing masks, and the implications of new privately run infrastructure like 5G will be potentially open to daylight robbery. There is likely to be new taxation, initially argued to help pay for the recession, but with perhaps ulterior motives.

Furthermore, we should be aware of new powers granted to government by themselves which, although on the surface might be enacted to temporarily suppress the populace, they may not be repealed completely or in part until some time into the future.

Show Comments +