The 1970s are often referred to as “the decade that style forgot”. Look at men’s fashions of the time – not just the elephantine bell-bottomed trousers, but also oversized lapels and collars on jackets and shirts. If you lived through it, as I did, it seemed as if everything which wasn’t corduroy was velvet – car interiors just as much as domestic furniture, clothing and even the occasional wall covering. And, please, can we not talk about platform-soled boots and shoes?

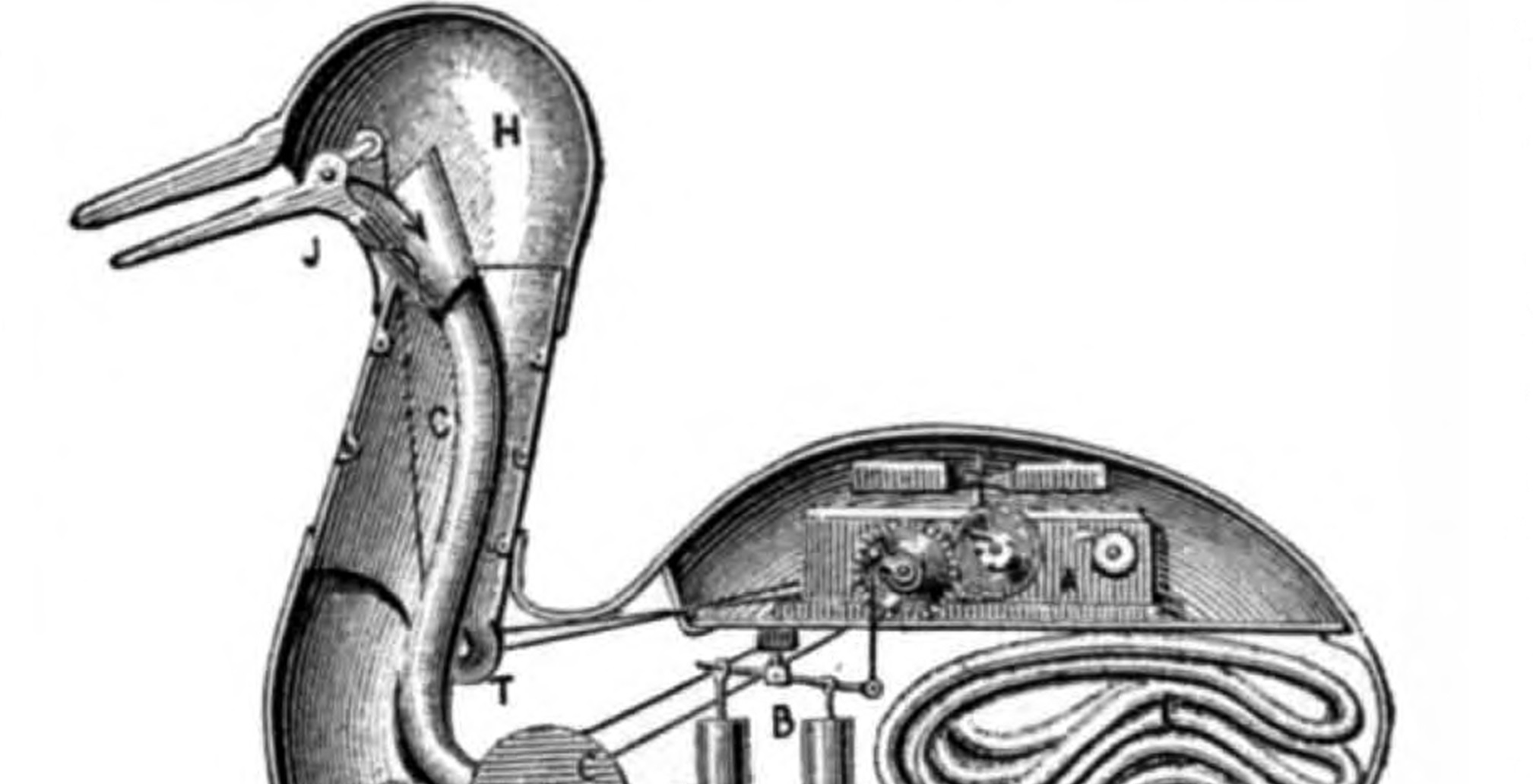

The clunky, oversized first generation quartz watches appeared at the right time – or did they? In fact, their oversized proportions were forced upon them by their innards: Switzerland’s first production quartz movement, the Beta 21, which measured a colossal 30.9mm x 26.5mm. Yet somehow the cases which surrounded this movement were unbelievably diverse in their design – there were simple round cases, oval ones, portrait as well as landscape format rectangular ones, hexagonal as well as octagonal and even wedge-shaped. The diversity of design came not from a desire to follow fashion, but instead it was a function of how the Swiss watch industry functioned at this time.

The Rolex 5100, known as “The Texan”, was priced in line with a fully equipped BMW 2002tii…

What is difficult to understand now is that when the Beta 21 was launched in 1970, there were no watch designers. Watch manufacturers actually just made movements – the cases and the dials came from firms who specialised in their production. These firms employed designers for their specialist components and watch manufacturers would be presented with a choice by the suppliers. The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak is always proffered as the world’s first luxury sports watch, but its much more important accomplishment was to be the first where the case, dial and bracelet were designed as a coherent whole.

When the case designers were presented with this new movement design they were given three pieces of information: that these new watches were not to look like others currently on sale, that they were going to be very expensive and that they were likely to have small production runs because they were exclusive, flagship watches. To give you an idea of how much so, consider this: the highest priced mechanical watch in the Rolex line-up at the time was the 18kt Day-Date and it sold for CHF5,975 (at that time, about £1,000) on a gold President bracelet. The Rolex model 5100 using the Beta 21 movement sold for CHF14,600 in yellow gold, and an astounding CHF18,300 in white gold; this converted to just over £3,000. The Rolex Day-Date was around the same price as the new Ford Capri, whilst the Rolex 5100 was priced in line with a fully equipped BMW 2002 tii. The Patek and IWC versions were even more expensive.

The largest wristwatch ever produced by Patek Philippe: ref. 3587…

Of all the major manufacturers, only Patek made its own cases. Whilst Rolex did have the facilities to produce them at its Genex plant in Geneva, the quantities were too small for them and so they had them made by the famed Geneva casemaker F Baumgartner who had created many of the most iconic cases for Patek Philippe. The IWC Da Vinci cases were produced in La Chaux de Fonds by Classicor SA, who made cases for everyone from Longines to Zenith. Interestingly many sources say that these were made in Italy by Fontana, but the Swiss Poinçon de Mâitre stamp of Classicor is clearly visible inside the case back. The only possible explanation for this misunderstanding is that the bracelet may well have been made in Italy.

The styles varied from outrageous to conservative and the interesting fact is that several companies chose to hedge their bets on styling by selling the Beta 21 in both flamboyant and also discreet styles. Patek’s offerings were the exuberant 3587 in a lugless television shaped case and its more restrained cousin, the 3603. Omega offered the wedge shaped Pupitre, with its tiny crown on the left and the more conventional model 396.0807, whilst daring IWC offered two models, the Da Vinci and the Disco Volante (incidentally the only Beta 21 watch ever made in sterling silver) as well as the much more bourgeois International.

Da Vinci Calendar with Beta 21 movement, one of the two models offered by IWC…

Whilst the big names tend to be the most collected and valuable – for example, I mentioned that the white gold Rolex 5100 cost the same as a BMW tii when new, and right now its value has risen to the same price as a brand new Porsche 911 – I suggest looking at the smaller brands for an everyday watch. The octagonal Bucherer, with its faceted case, “Eagle beak” indices and orange dial accents is a gorgeous looking watch which could have been launched last year rather than half a century ago, whilst the Rado, with its huge bracelet links, lapis lazuli dial and amazing applied steel indices could not be more redolent of the 1970s unless it wore bell bottoms and a bomber jacket with a fake fur collar. And though the Omega Pupitre is one of the better-known models, it can easily be found, along with the two watches mentioned above, for £4,000 or less.

But I would be remiss if I suggested that only the Beta 21s are worth looking at. Some of the watches which came after these – such as the “Casquette” from Girard Perregaux, the first Swiss LED watch – have become highly sought after, as have many of Seiko’s high-end quartz watches from this period; their amazing interplay between angular and circular planes and the use of brushed and polished surfaces are a lesson to us all in case design.

First ever Seiko Quartz Astron produced in 1969 featuring a 35SQ movement…

However, if I had to emphasise an area on which to focus for the collector, it would have to be on the Beta 21s, and for a number of reasons. Firstly, they are horologically important, quartz being the most relevant development in the history of timekeeping in the 20th century; secondly, they are stylish and look unlike almost every watch being made today; thirdly, they are quartz watches which do NOT bear the stigma of a stepping seconds hand – it sweeps as smoothly around the dial as any mechanical watch. And finally, because of their oversized proportions, foisted upon the case designers by the huge movement, they look absolutely current with today’s design environment.

Opening picture: Omega advertisement from 1970 (image cropped from the original).

Show Comments +