If you’re a fan of great 14th century Italian art – and who isn’t? – you might want to consider camping outside the National Gallery for one of the most eagerly anticipated cultural events of the year.

Marking the 200th anniversary of the National Gallery and paying tribute to the earliest pictures in its collection, Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300 – 1350 is a seriously impressive exhibition. It reunites many of the greatest works in all of Western painting – some for the first time in centuries. A number of the most groundbreaking pictures in the history of art, many of which formed part of larger ensembles before being dismantled, are being brought back together at this rarely- staged exhibition.

These highly prized, enormously influential and innovative paintings, many in gold ground, will be on display at this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition of Sienese art from the first half of the 14th century. The exhibition of approximately one hundred works illustrates how the status of painting developed during that period and underscores the central role that Sienese artists took in that story. For the first time in history, faces showed emotion, bodies expressed movement, drama, in short, was introduced into painting.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà – Panels, 1308-11. Left: Christ and the Woman of Samaria. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Right: The Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The most exciting news is that in this show, several surviving panels from the gigantic double-sided masterpiece known as the Maestà (Majesty) have been reassembled for vistiors to admire. Painted by Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna (active 1278, died 1319) for the city’s cathedral in 1308, this sublime work is the first double-sided altarpiece in Western art. Broken up in the 18th century, this astoundingly complex, monumental piece represents a seismic shift in narrative art.

Thanks to loans from around the world, the National Gallery’s own three panels from the Maestà will once again hang next to several other paintings from this exquisite ensemble depicting episodes from the life of Christ. It’s a thrilling prospect.

If I were you, I would start pitching your tent in Trafalgar Square right now.

Author: James Rampton

Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350

8th March-22nd June 2025

The National Gallery

More information and tickets, HERE.

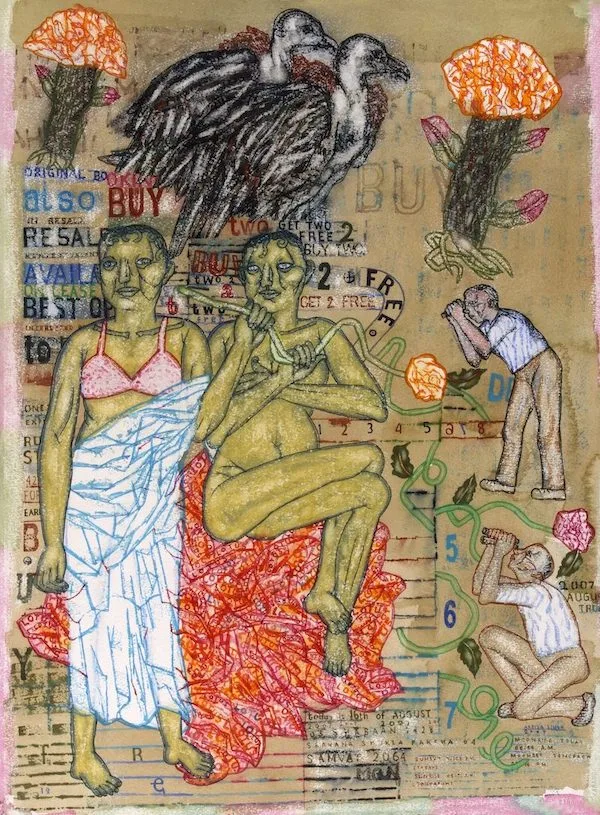

Lead image: Duccio di Buoninsegna, Triptych with the Crucifixion and other scenes, c. 1302-8. The Royal Collection / HM King Charles III. Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024. Image cropped from the original due to formatting restrictions.

Read about other unmissable exhibitions this season: The Oskar Reinhart Collection, at The Courtauld, London; Anselm Kiefer: Early Works, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; and Arpita Singh: Remembering, at the Serpentine North, London.