On August 9, 2008, a smartly dressed and heavily pregnant lady walked into Zion Yakubov’s shop in Tel Aviv and presented him with a shoebox filled with some items that she wanted an opinion on for insurance reasons.

The Queen returns

Yakubov opened the box and could not believe what he found. Although he was not a noted horological expert, he knew what he was looking at: a number of watches from the L.A. Mayer Museum where the foremost collection of Breguet watches had been held, donated by the Salomons family through their daughter Vera Bryce. 25 years earlier, the museum had been robbed in a daring operation and none of the watches had been seen or heard of since. So, what happened? Where were the watches all that time if they were not for sale? After the robbery, the security forces were sure that the watches had been broken up for their precious metal and gemstones. Yet, here they were, in a non-descript shoebox, wrapped in tissue paper and with most of them working.

The Breguet 160 “Marie Antoinette”

Abraham Louis Breguet was the foremost watchmaker of his age, perhaps of any age. His list of accomplishments in horology is testimony to the fact. His contributions went far beyond invention and manufacture. In the words of George Daniels, who was arguably a 20th-century equivalent, “His contribution was as brilliant as it was original and, during a period when horological fashion was the slave of science, he lifted it to a new dimension of visual and technical excellence.”

Because of that, Breguet also became the preferred and at one point officially appointed watchmaker to the French Court. He was fortunate that Marie Antoinette was fascinated by watches. It was one of the few objects she had brought with her from Austria. Timepieces were a personal gift and none were more treasured than those made by Breguet at his atelier in Quai de Horologe.

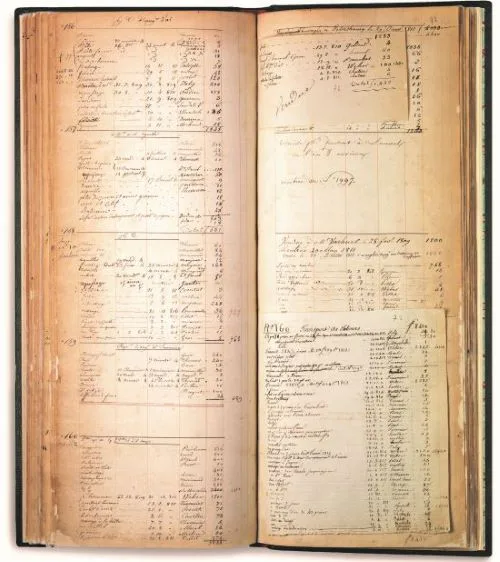

Breguet’s ledger kept meticulous details of all orders.

He kept meticulous records in his ledger of who ordered them, what was required, and whom they were for. The 160th commission, dated 1783, describes the most complicated watch conceived at the time and which remained horology’s most complex mechanism until the last century. The entry reads “with the condition that all the complications possible and known be incorporated in it. Everywhere, gold must completely replace brass. No limit on manufacture or price was imposed.” The watch was to be a perpetual calendar, perpetually wound, a symbol of everlasting love worthy of a queen.

The name of the commissioner and the intended recipient were, unusually for Breguet, left blank. Although there is no evidence to confirm it, the watch is believed to have been an intended gift from Count Hans Axel von Fersen, a Swedish officer, and nobleman at the French Court who allegedly was Marie Antoniette’s lover. He was also the man who organised the failed attempt for the French queen’s escape from her revolutionary captors. Fersen himself died at the hands of an angry mob in Sweden 17 years later. Watches in the court of Louis XVI were a gift of love. Fersen and Marie-Antoinette had both previously commissioned pieces from Breguet, but nothing on the scale of the 160.

Whoever ordered the watch and whomever the watch was intended for, did not see its completion. Neither did Abraham Louis. The watch was completed by his son in 1827, four years after his death. When finished, it was an encyclopedia of his life work. Everything he had learned was within that one piece, about a dozen complications and inventions that are still being worked on today. The 160 was sold in 1887 to Sir Spencer Brunton after the first owner returned it for service and failed to collect it! Eventually, it ended up in the collection of Sir David Lionel Salomons, who acquired the watch in 1920 and bequeathed the piece, along with 57 other Breguet timekeepers, to his daughter, who in turn, donated the bulk of her father’s considerable collection to the L.A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem.

The original 160, a watch fit for a queen.

Night at the Museum

According to Ezekial McCarthy of the Jerusalem Police, the robbery at the L.A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in 1983 was the result of a well organised and professional gang. They had broken in undetected, selected the most valuable and the very best of the collection, and escaped leaving no trace. The detectives were sure that the watches would be sold for the value of the precious stones and metals. There was even speculation that the robbery had been to order for a set of large and prominent collectors.

In fact, the robbery was carried out by just one man: Na’aman Diller, a former Kibbutz and Special Forces operative. He was otherwise known in Tel Aviv as the “Kibbutznik burglar”. Something of a loner, this slim, awkward, and tenacious man had never fitted in with the military and after working on a Kibbutz, had taken to a life of small-time crime; always working alone.

On the night of April 15, 1983, Diller drove his car to the gates at the back of the museum, walked across the road and started to work on opening up the bars to the window at the back of the building using a crowbar. Once the bars had been pushed apart, he had direct access to the room with the watches. He sound-proofed the room against the rest of the museum and installed a microphone to listen for guards. He then methodically and systematically went about taking the most desirable pieces from the display cabinets. He knew which ones were the most valuable from a museum book cross-referenced with auction catalogues.

He brought in some food and soft drinks and each time his rucksack was full, he would unload the precious cargo outside, go back in, take some more, and repeat the production line until morning. Throughout the night the security guards did not think to check on the locked room containing the watch exhibits. While everyone, including the police, thought that the alarm system had been disabled, the truth of the matter is that there was none. Something Diller had been able to figure out by himself. Apparently, discussions concerning the security system had been protracted over a decade previously and because no consensus could be reached, no alarm had ever been installed.

Raid in Tarzana

One early morning in May 2008, an L.A.P.D. SWAT (special weapons and tactics) police van pulled up in a quiet street in a Los Angeles residential district of Tarzana. Their intended raid was to be on a small house that was reportedly occupied by a fugitive: Nili Shamrat, a tenth-grade teacher at a local Jewish school who may, according to L.A.P.D., have been armed. A SWAT team circled the dwelling and when in position, the lead officer knocked on the front door with the statutory police greeting of “armed police officers are about to enter the building.” To their surprise, a thin diminutive lady answered the door and invited them in. They questioned her about Diller and any items that he may have stolen and left with her. Her initial response was to deny there were any goods from Diller; on inspection, some paintings and an antique Latin manuscript were found, but no watches.

Most of them turned up in safety deposit boxes in places as remote as Israel, the Netherlands, and even the United States. 96 of the 106 stolen pieces turned up. The Breguet 160 was among them, completely intact. No one is sure why Diller undertook the robbery, perhaps to get equal doses of wealth and notoriety for Israel’s greatest ever heist. No one knows his true motive, since he held onto the 160 until his death. He also held his silence on his motive.

Diller certainly tried his hand at selling some of them. He attempted to enter Switzerland by train but was turned away by the customs and excise guards. Perhaps the most surprising discovery, when the museum recovered the watches, was the small pieces of paper within the mechanisms and the homemade bottles of oil in the boxes. Over the years, Diller had been maintaining and repairing the watches on his own. Learning how the different parts worked; what needed to be oiled and what did not and leaving notes to whomever came after him as to what to do with them to keep them in running order.

Interviewed by John Biggs for his 2015 book “Marie Antoinette’s Watch: Adultery, Larceny, and Perpetual Motion” Nili Shamrat, Diller’s widow and long-time love from his early days in the Kibbutz, noted that in the later years of his life, Diller had been more at ease. He ended up living in Tel Aviv, she in Los Angeles. He would phone her every morning when they were apart and Nili would spend the summers with him in Israel. Over time, his initial intention to sell the watches for their raw value turned into a desire to preserve them and learn from them, probably developed over the long months in which his only contact with Nili was their daily phone call. The 160 particularly captured his imagination and so, he spent years studying its complexity and I suspect, falling in love with it. Inadvertently, the Breguet 160 had become an object of affection once more, and in a far humbler setting.

Breguet 1160, a modern replica of the 160, produced in 2008.

Aftermath

Before his death, Diller showed Shamrat the L.A. Mayer museum and the room where he conducted the robbery. He also told her of the boxes in his apartment and in storage. In trying to do the right thing and return the museum’s property, Shamrat was ultimately charged in the U.S. with receiving and dealing in stolen goods. She lost her job at the school in Los Angeles.

The Breguet 160 sits once again in pride of place in the Salomon Room inside the L. A. Mayer Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem. Protected behind every modern conceived security device and under constant surveillance, “The Queen”, a symbol of affection and love lost, stolen and found again, is now secure.

Words: Dr Andrew Hildreth

Opening picture: Queen Marie-Antoinette à la Rose by Vigée Le Brun.

Show Comments +