The BFI was founded in 1933 and the BFI National Archive in 1935. It is considered one of the largest collections of film and television in the world. It holds 180,000 fiction and non-fiction films and 750,000 television programmes; and is an inspiring resource for a new generation of young and talented British film makers. The collections held in the archives are a fascinating record of history, culture and the art of film making and TV production.

The team at the BFI, led by Head Curator Robin Baker and Head of Conservation Charles Fairall, are totally dedicated to finding and preserving lost film treasures, not only British film, but from all over the world. Using the latest preservation methods, the conservation team cares for a variety of obsolete formats so that future generations can enjoy the rich heritage of ours and indeed world cinema. Sadly, not all films survive. One of the most important films still missing is Alfred Hitchcock’s Mountain Eagle (1926) which is on the BFI’s ’75 most wanted’ list of lost British films. In 2012 the BFI undertook its largest restoration project to restore ‘the Hitchcock 9’, that is, Hitchcock’s surviving silent movies.

“Preserving films for the future is not just about looking after old movies,” explains Robin Baker. “One of the most rewarding aspects of our work is acquiring the best of contemporary British filmmaking and making sure that it is fully preserved. We live in a digital age, but digits are even more vulnerable than 35mm film. Persuading some filmmakers to donate copies of their work can be challenging, but we need to ensure that their films are safe 200 years from now. If we don’t get them into the archive, who knows what will survive in just a few decades.”

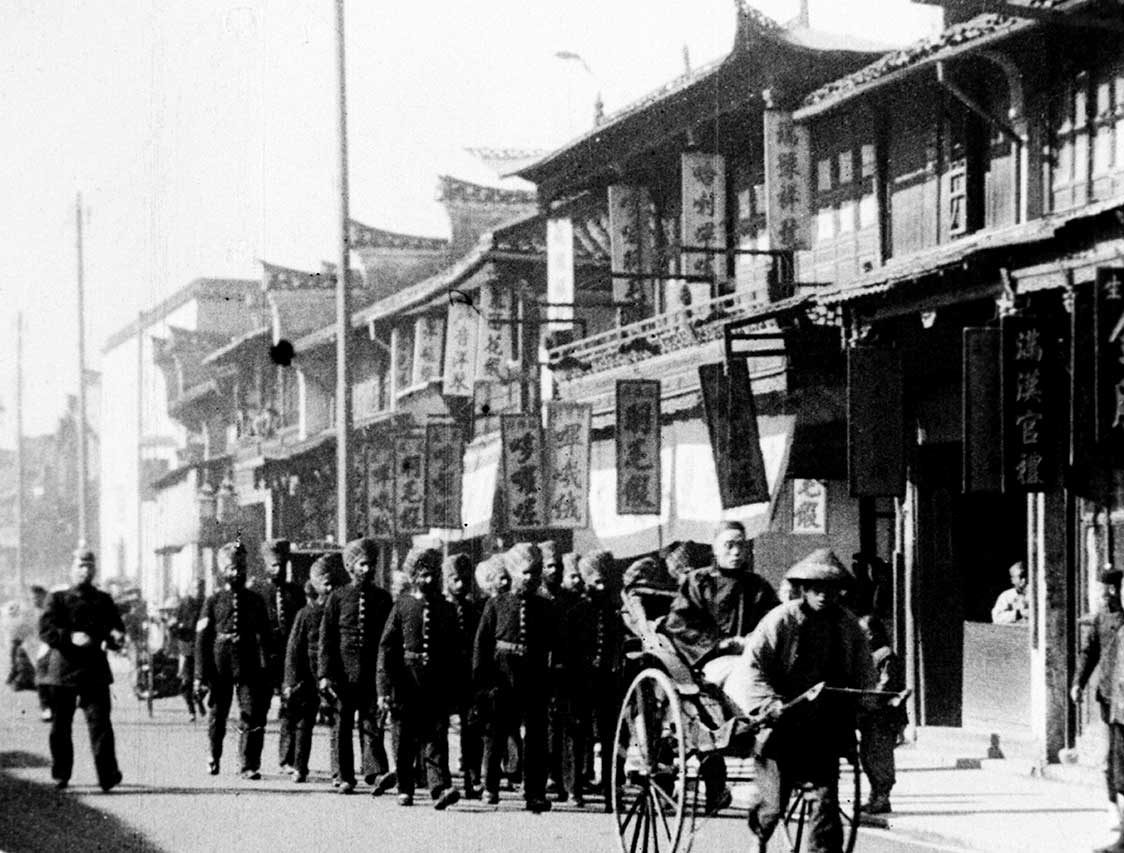

The BFI has also beautifully restored footage filmed in China between 1900 and 1949, making them available to new audiences. An excellent example is the hugely successful project Around China With A Movie Camera. Some of these films may have never been seen in China as it was taken by a series of French and British film makers. Much of the unseen footage was taken by amateurs and early intrepid tourists. One of the most startling and beautiful restored pieces is the film Piccadilly (1929), staring Anna May Wong. In addition, the BFI restored one of the first films of China known to have survived anywhere in the world, Nankin Road, Shanghai, shot in 1901. Not seen for 113 years, a copy of this beautiful film was presented by HRH the Duke of Cambridge to Mr. Ren Zhonglun, Chairman and President of the Shanghai Film Group Co. Ltd and to Mr. Miao Xiaotian, President of the China Film Corporation. This alliance has now led to a landmark film Co-Production Treaty between China and the UK.

When asked about the fun part of the job, Robin Baker comments: “The most exciting part of my job is being in the position to give new life to old films. In 2015 we launched a huge online project called Britain on Film, making available thousands of films that tell the stories of the people and places of Britain. To date they have been watched by over 25 million people. I find it enormously rewarding that film heritage is enjoyed by so many people who want to discover more than just the latest feature films.”

Another extremely exciting find was the discovery, in a chemists shop, of what was thought to have been lost to the nation forever: hundreds of Edwardian films of everyday life in the North and North West of England made bi pioneering filmmakers Mitchell and Kenyon. They would shoot footage of everyday life and then invite the people of the town they had filmed into a circus tent to watch the film footage. These films give us a unique insight into the past and potentially into our ancestors. The BFI Player allows anyone to watch some of the Archive’s film collection online; and thanks to the BFI’s Britain on Film project, over 7,500 films have been added over the past three years. There is an interactive map to click on towns and villages all over the UK, so you could end up watching films from where your family originally came from and God knows what you could discover!

The BFI Archives also contains a wealth of costume designs, such as those designed by Cecil Beaton for Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady and his designs for Vivien Leigh in Anna Karenina. It does not stop there, with 30,000 unpublished scripts, movie posters and so much more, it is an Aladdin’s cave of treasures.

Funding is a very important part of the BFI and its National Archives. Restoring film is expensive. The cost depends on whether it is black and white, colour, the conditions it’s in… so costs can vary enormously from £10,000 for a black and white 70 minutes feature up to £200,000 plus for a 2 hour Technicolor film. So funding is truly vital. John Paul Getty Jr was the single most important benefactor in the BFI’s history. By the time of his death in 2003, his generous donations had enabled the opening of a purpose-built conservation centre, as well as securing the BFI’s headquarters in London. In recognition to his generosity, the Archive is now called the BFI John Paul Getty Jr Conservation Centre.

The BFI is a registered charity and funds its activities through a mix of Grant-in-Aid from the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and self-generated income through sponsorship and philanthropy, sales and distribution. Additionally, it gets funding from the National Lottery fund for film across the UK. Companies like IWC Schaffausen and American Express play a key role in helping the BFI finance their work, and enables it to be a leading light in film education, nurturing young and up and coming talent and giving generations to come a continual appreciation and inspirational journey of films from the past and into the future. One of the most glittering events organized to raise funds for the BFI to continue its work is the LUMINOUS gala, held by the BFI every two years, in partnership with IWC Schaffhausen.

This partnership has brought together some of the most recognised stars of stage, film, and TV. Luminous Champions include Dame Judy Dench, Lord Fellows, Tom Ford, Martin Scorsese, Sir Michael Caine, Dame Maggie Smith and the late Sir John Hurt to name but a few. This star studded event has helped raise hundreds of thousands of pounds. In 2015 they raised over 430,000 pounds net. This money financed the restoration and release of epic and powerful films such as Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) and Franz Osten’s Shiraz (1928). The nest LUMINOUS Gala will be held at the Guildhall on October 3rd 2017, on the eve of the Opening night of the 61st BFI London Film Festival. The evening will be hosted by Jonathan Ross with Tilda Swinton as guest speaker.

This is also the night that the second IWC Schaffhausen Filmmaker Bursary Award in association with BFI will be presented. This is an award aimed at nurturing the talent of the UK’s new and emerging film makers. Last year’s award went to Hope Dickson Leach, director of the thought-provoking film The Levelling, which premiered at the BFI Film Festival in 2016 and was released to great acclaim. This year’s shortlisted nominees are yet to be announced and the winner will be presented with the bursary at LUMINOUS by Oscar-winning Director Tom Hooper.

Meticulously restored by the BFI National Archive, Franz Osten´s Indian silent epic Shiraz (1928 ) will

screen at the Archive Gala of the 61st BFI London Festival in partnership with American Express on October 14th. This is a stunning piece of cinema, telling the love story of one on India’s most famous princesses, whose beauty inspired the Taj Mahal. The film will be performed live with a newly commissioned film score by the daughter of world famous Ravi Shankar, the multi Grammy-nominated Anoushka Shankar. In partnership with the British Council as part of the UK-India Year of Culture, the BFI plans that Shiraz can once more be shown in the beautiful country where it was originally filmed.

I’ve frequently heard the question ‘Why preserve movies?’ And my answer is always the same: how can we not preserve movies? The cinema is more than our culture – the cinema is us.

Martin Scorsese

Show Comments +