Sixty million soldiers from all over the world served in Word War I, fighting in locations all over the planet, from France to Greece, Turkey to China, the North Sea to the Pacific Ocean. The acceleration in the development of warfare technology at the end of the 19th century meant that combat in WWI became a unique and terrifying experience.

In the UK around six million men were mobilised during WWI, and of those, 890,000 died during the war. Over 16,800 civilians also lost their lives. A lot has been written about the famous battles of the Great War: Somme, Marne, Gallipoli, Amiens, but only the valour of a few men has been recognised: Alvin York, Henry Johnson, Alan Jerrard, and even a woman, Edith Cavell, a British nurse who helped 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium. But what happened to the other millions of soldiers that dutifully and bravely served day after day in the front line? What happened when men, often not even 20 years of age, were given the order of ‘going over the top’?

One such man was George Edgar Hildreth, the son of the local blacksmith in Prestwood, Buckinghamshire. The Hildreths have been in the area for a long time and had been instrumental in the development of the village, contributing with most of the ironmongery for public buildings, including that for the Church. Such was their presence in Prestwood that there is even a Hildreth lane today, a Hildreth’s Garden Centre and a Hildreth’s Hardware Store.

When WWI started in 1914, his brother Harry stayed to look after the blacksmith shop and George signed up to go to war. He joined the rifles, the South Wales Borderers and was trained at Bisley, at the Royal Regiment training grounds in Surrey, to become a sharp shooter. In Sebastian Faulk’s famous novel Birdsong (1993), the author focused in how the experience of trauma shapes individual psyches. One of the main characters is a miner who, in 1916 France, was a soldier ordered with digging out the explosives in no man’s land, so they could blow them up remotely and move on.

Sergeant George Edgar Hildreth was doing the opposite. As a sniper, he was out there in no man’s land, wading through the mud, the blood and the bodies that were lying around, to position himself, looking to mark Germans and take them out, one by one. That’s what he did from 1914 to 1918. He was 6ft 6’, hard to miss. However, he had to keep cool, crawl, and slither, and somehow, he managed to survived unscathed for three and half years. He was posted to France, to the trenches, as part of the Western Front. Landing in Le Havre in 1914, he was deployed first to Ypres and from there, later in the war, to the Somme.

For the soldiers of WWI, combat was an exceptional circumstance, rather than the norm. For many, life consisted of toiling to keep those at the front supplied. One could even say that frontline troops had not too bad a life, as they were regularly rotated to make sure that the time they spent facing the enemy was balanced with time spent at rest, even going on home-leave. As a frontline soldier, Sergeant Hildreth’s every day life was pretty much the same, the sodden squalor and listless life of facing forward until day’s end: live in the trenches, go out, set up your position, settle, take aim and shoot. The only respite was the occasional leave to go home and see his wife.

That said, the reality of life in the front was much harder

That said, the reality of life in the front was much harder. Men were exposed to the elements for days or weeks on end, with limited shelter from cold, wind, rain and snow in the winter or from the heat and sun in summer. Artillery destroyed the familiar landscape, reducing trees and buildings to desolate rubble and churning up endless mud in many areas. The deafening and disorienting noise of artillery and machine gun fire, both enemy and friendly, was incessant. It is true though that in some quiet sectors there was little real fighting and a kind of informal truce could develop between the two sides. Even in more active parts of the front, battle was rarely continuous and boredom was common among troops, with little of the heroism and excitement many had imagined before the war.

On the other hand, the men and women who served in WWI endured some of the new brutal forms of warfare ever known. Millions were sent to fight away from home for months, even years at a time, and underwent a series of terrible physical and emotional experiences. The new technologies available to WWI armies combined with the huge number of men mobilised made the battlefields of 1914-18 horrific.

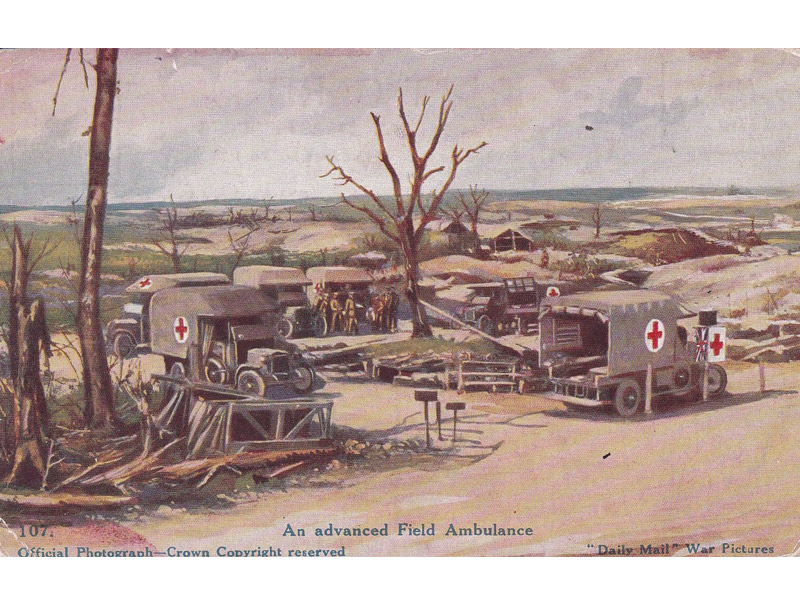

Men ordered to attack – or ‘go over the top’ – had to climb out of their trenches, carrying their weapons and heavy equipment, and move through the enemy’s “field of fire” over barbed wire, keeping low to the ground for safety… and avoiding landmines. The objective was to reach the enemy’s front line, and use rifles or bayonets to attack the enemy directly in their own trenches. Once the defenders were eliminated, the attacking force seized the position… in theory. In reality, these tactics were often unsuccessful and victorious attacks were rare, ground gained by attrition; every inch was earned in the blood, sweat and tears of the men who fell to provide the way for their fellow soldiers. Casualties were extremely high, with many men killed and wounded: attackers often suffered higher casualties than defenders. Wounded men were carried or escorted back to field hospitals for treatment, while the dead could only be buried if there was a break in the fighting.

In January1918, Sergeant Hildreth was shot in the head and presumed dead. A telegram was sent to his wife from the War Department saying:

Sorry to inform you that your husband made the ultimate sacrifice to your country and died in combat. Thank you for your sacrifice…

Unknown to all of them, Hildreth had spent two days crawling in the mud and rain with a massive head injury, cold, alone, disoriented and scared. He finally arrived to a French field hospital where he was treated.

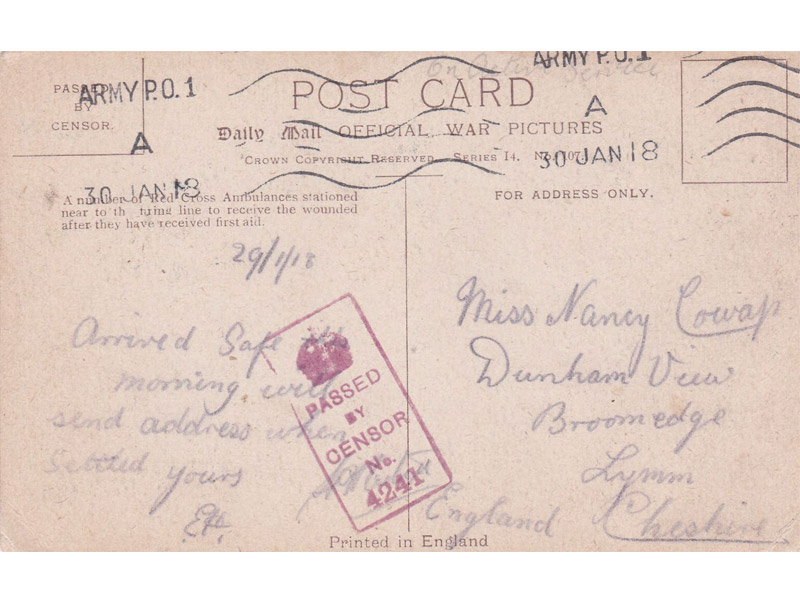

Three weeks after the telegram from the War Office, a postcard and letter from him arrived to his wife saying, “I expect you’ll be surprised to get this letter from me, dear, but I thought I’d let you know that I was slightly wounded in the face and shoulder but nothing serious.” Where this man found the courage and presence of mind to write such a letter, I can’t imagine. After that, he was dismissed from service and went back home. In this day and age, when information arrival is almost immediate, it is hard to comprehend that someone could be presumed dead; that actually measures were undertaken to finalise the life of Sergeant Hildreth, and yet, he was alive and reliant on a postcard from a hospital bed to prove he was still among the living.

Sergeant Hildreth’s only son, George, was born in 1925

Hildreth took a short break and then went to train other sharp shooters at Bisley, before joining Scotland Yard in 1921. He was given Detective status, and put in charge of the Prime Minister’s security at Chequers all the way through the 1930s. Sergeant Hildreth’s only son, George, was born in 1925. Despite peace and the uneasy overtures of hostilities returning to Europe, it was the smallest and most hidden of killers that bettered George Hildreth in the end. In 1937 Hildreth refused to leave his post as Head of Security at Chequers, despite of having a bad cold, which turned into pneumonia and eventually, killed him. Just months before penicillin became widely available and in the prime of his life, Sargeant Hildreth’s life was cut short by an invisible enemy.

Show Comments +